I hadn't intended to write anything on the great comic book artist Jack Kirby, who would've been 97 today if he hadn't died in 1994 (I always find it odd when someone wishes a dead person a "happy birthday" as if they care--commemoration I understand, but celebration?). Then I came across enough other mentions of it that I thought I could muster a Facebook quip, then enough others that I thought I could make a post of it. And here it is.

Kirby represents a lot of things to the comics industry, and has come to represent more since his death. In his time, he was a dynamic storyteller whose style was unique and unmistakably his. Along with Stan Lee, Kirby built Marvel Comics in the 1960s. The X-Men, the Fantastic Four, the Silver Surfer, Captain America, Thor, the Hulk, the Avengers: without Kirby, they'd have been very different or not existed at all (I pointedly omitted Spider-Man and Iron Man, whom Kirby had little to do with). Perhaps more importantly than the multitudes of characters he created, Kirby brought a grandeur and pop-art respectability to comics. He made them cool, even for adults.

That is not a trivial accomplishment.

In later years, Kirby became estranged from Lee and Marvel, and switched his allegiances to DC Comics, where he wrote and drew some of the strangest Superman and other stories ever told. Without a writing partner to rein him in (or stifle him), Kirby produced some pretty wild and crazy stuff--not all of which I'd call "good" but ALL of which was interesting, worthwhile and, again, uniquely, idiosyncratically Kirby. Questions of "plot," "story," "logic" and "characterization" fall by the wayside when you're being punched in the face by a four-color dynamo.

|

| One of those weird Superman stories. |

After his passing, Kirby became the quintessential "Comics Creator Done Wrong." Comics were a different business when Kirby got his start in the 1930s and '40s, and aren't celebrated for their enlightened labor policies even now. It goes without saying--and yet is still occasionally argued in court--that writers and artists like Kirby had no ownership of the characters they created. It's called "work for hire." There were no royalties or profit-sharing. Kirby's creations have made billions of dollars for movie studios and shareholders, millions of dollars for the actors hired to portray them, and comparative pennies for Kirby and his heirs.

Generally, I don't like judging people and practices of the past by the standards of the present (yes, horrified future citizens of the 22nd Century, I burned fossil fuel and ate meat!). Times were different. The business was different. Expecting a 1940 pulp-paper publishing house to live up to 21st-Century intellectual property ideals seems grossly unfair to me. STILL...a movie studio could slip 1% of Robert Downey Jr.'s paychecks to the Kirby family and set them up for life. S'all I'm sayin'.

Writer Mark Evanier, who worked as Kirby's assistant, often says that Jack saw it all coming: ideas from the comics spilling into other media, mainstream acceptance, movies and TV adopting the language and spectacular imagery of comics as soon as their technical capabilities caught up with the imaginary vistas one man could conjure with a pencil. None of the current success of superheroic entertainment would have surprised him.

Like a lot of comic book readers, I didn't like or get Kirby when I was a kid, being more impressed by the "realistic" illustrative styles of artists like John Buscema or Neal Adams. As often happens, as my sophistication as a comics consumer (and later, a comics creator) grew, so did my esteem for Kirby. His imagination was unparalleled, his output prodigious. His work is pure, distilled, iconographic comics ENERGY.

Comics journalist Tom Spurgeon posted a nice large gallery of Kirby artwork, which represents just a tiny fraction of his output. Rather than duplicate Tom's effort, I'll post one of my favorite Kirby pieces that doesn't have any superheroes in it at all. I saw this in the beautiful big book Kirby: King of Comics written by Evanier (and edited and published my my editor and publisher). I don't really know Mark but I've met and talked with him a few times, and when his book came out I told him there was one page in particular that really knocked my socks off. He knew exactly which one I meant without me saying another word.

It's a double-page spread from a story titled "Street Code" drawn in 1983. This is Kirby's pencil art, not yet inked for publication. The detail in this is incredible. Astounding. Even more impressive is how those details are composed so that the setting and all the action are perfectly clear. Areas of black and white guide the reader's eye around the page exactly as Kirby intended, taking in a dozen different dramas in this theater of the street. So much rich detail, from the prices of the fruit to the architecture of the tenements, yet there's nothing muddled about it.

There's also some typical Kirby wonkiness in this drawing. Kirby approached human anatomy as more of a suggestion, and his perspective could be very . . . impressionistic. For example, that car on the right is huge and the back of that horse-drawn ice wagon is nearly two stories tall. Those are not flaws that need to be fixed. Those are Kirby. When the rules get in the way of storytelling, the rules lose. Being "better drawn" would not make it a better comic.

Jack Kirby was a comics giant who needs to be remembered and appreciated. I guess his birthday is a good day to do that.

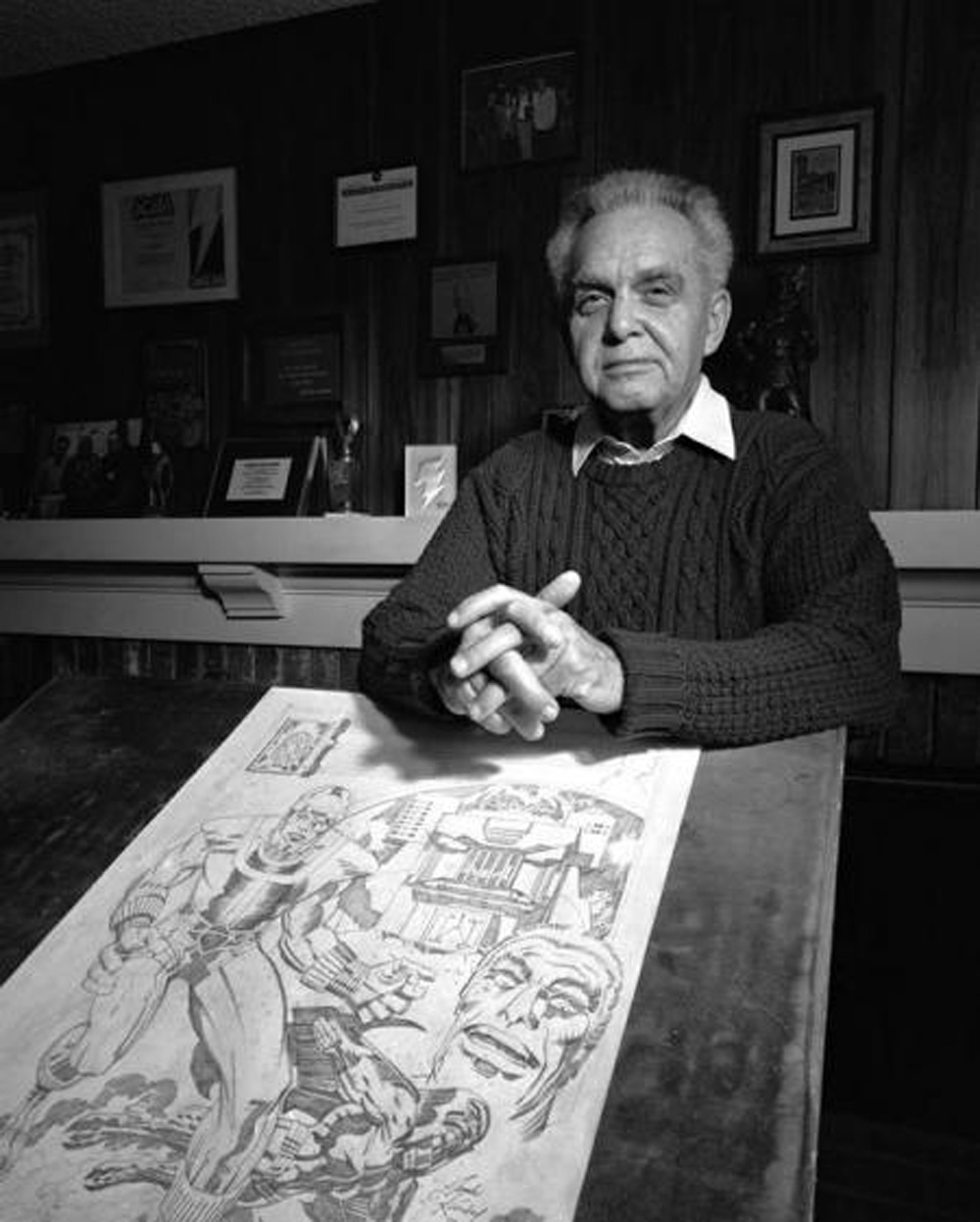

|

| Photo by Greg Preson, I'm informed. |