The Last Mechanical Monster. A Fire Story. Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow? Mom's Cancer.

Monday, November 28, 2011

How Some Other Guy Does It

1. I pencil with "non-photo blue" pencil rather than regular graphite. Because light blue pencil doesn't scan well (it's practically invisible), I don't have to erase the pencil lines, which can smudge and dull the black inks. Any blue lines that survive scanning are easily deleted in Photoshop.

2. I ink mostly with a brush rather than a pen, although I do use an ink nib like his or Pigma Microns for fine details and ruled lines.

3. I don't do a coffee wash (!). In fact, I wouldn't even if I wanted to. My goal is to produce crisp black-and-white line art with sharp edges and no shades of gray (or anti-aliasing) that I can then shade or color as needed. It prints much better. If I did want to lay down a wash, I'd do it after I'd scanned the inked line art to superimpose pure blacks over the wash.

If you're interested in how comics get made, I endorse this process as ONE good way to do it.

Incidentally, in the good old days (i.e., the 20th Century), lettering would've been hand-inked directly on the page before anything else, between the penciling and inking steps shown here. That's how I did Mom's Cancer, and how a dwindling number of cartoonists still do it. What Kody does in the video, and I did in WHTTWOT, is digital lettering, performed with Photoshop after the art's been inked and scanned.

Here's the key: even though these days lettering is one of the last elements completed, it should still be the first thing you think about when laying out the page. Words pull the reader's eye through the story, and the word balloons have to flow from one to the next effortlessly. Before you start to draw, decide where the words go. Poor word placement and lettering is a fundamental error common to bad or amateur comics. It's very important.

Monday, November 21, 2011

My Old Haunts

Karen and I really appreciate the sympathy and support that we received here, on Facebook, and in person about our stolen car. Thanks. I think the people who called it "mean" best summed it up for me. Stealing someone's car is just a mean thing to do. Human beings sharing this little rock for such a short time simply shouldn't be that mean to each other.

I realize asking a car thief to pause and consider the epochal cosmic perspective might be a bit much.

Luckily, our insurance company is handling it well and we can roll with it financially. As I said, our beloved Honda was getting old enough that we were thinking of replacing her anyway (although we never discussed it within her earshot). So we went car shopping last weekend. Car technology has improved since we bought our Accord 15 years ago. Car salesmen have not.

Today's re-run is nearly five years old. I chose to post it today because it was originally inspired by a sighting of the constellation Gemini, which I happened to notice for the first time this fall a few nights ago. As you'll read, Gemini holds a special place in my heart.

One of the commenters on the original post was "TVDadJim," aka Friend O' the Blog Jim O'Kane, who wrote, "Watching Orion, though, usually gives me something like Galactic vertigo--because I know we're facing away from the cheery fireplace of the Milky Way's core, and out into the inky black of forever." Tell you what, Jim: you head for the black hole at our galaxy's center, I'll light out into the inky blackness the other direction, and we'll see which one of us is in better shape in a couple million years. Your "cheery fireplace" looks like a radiation-drenched gravity-shredding maelstrom to me, but to each his own.

(January 2007)

White Sirius glittering o'er the southern crags,

Orion with his belt, and those fair Seven,

Acquaintances of every little child,

And Jupiter, my own beloved star!

I was reminded of that (and of Wordsworth's epic poem, which I studied in college and is one of the few textbooks I've kept all these years) the night before last when I stepped outside and noticed Gemini rising in the east, over beside Orion. I can never look at the constellation of the twins Castor and Pollux without remembering another night almost 20 years ago, right after my wife and I found out she was expecting twins, when I looked up at the sky and smiled because I was looking at their constellation. Not their Zodiac sign (bleah), but the distant suns whose pattern in the sky would always remind me of the happy day I learned they existed.

I'm pretty sure that years later I showed my girls Gemini and tried to explain the significance it held for me. If I recall correctly, they were unimpressed. That's all right.

The reappearance of old friends in the sky marks the seasons for me: Antares, Lyra, Orion of course. My pals Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali, about whom I once made up a nifty ditty.* The fuzzy blotch of the Pleiades that always seems to catch me by surprise. I seek out the tiny, obscure constellation Vulpecula and remember freezing nights spent in a small university observatory doing photometry of a dim nova with my physics professor mentor who found it soothing to listen to WWV time signals pinging on the shortwave. And doesn't everyone have a favorite planet? (When I was a kid mine was Mars but I'd have to say Jupiter now, although I've flirted with Venus from time to time. Saturn's nice but just too ostentatious for my taste; I don't appreciate a show-off planet that tries too hard.)

Being in the habit of looking up at night gives me an agreeable perspective. There's the notion that somewhere out there, someone you're thinking about might be looking at the very thing you are (I believe astronomers call this the Fievel Mousekewitz Conjecture). Maybe even an alien looking at it from the other side, or looking past it at you. There's also the notion I've had while peering through a telescope that at that very moment I might be the only person in the universe looking at that particular thing. And there's always the "eternal circle of life" idea that you're just a point in a continuum of people who've looked at virtually the same moon, planets, and stars for millions of years and will continue to do so for millions more.

No profound conclusion. It's just nice to see Gemini again.

* Sample lyrics: "Zubenlegenubi, Zubeneschamali, yeah yeah yeah!"

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Like a Thief in the Late Afternoon

Did I mention that the thieves also stole the car?

Sometimes I bury the lede.

It was a bold crime, almost admirably audacious. Sometime between 2:30 and 5:00, somebody broke into and hot-wired our car while it was parked directly in front of Karen's busy office building. Daylight, people coming and going. Very gutsy. The car was a '96 Honda with more than 200,000 miles on it--the same car I wrote about last June--and wasn't worth much. But that model's one of the top three or four most commonly stolen cars because there's a huge black market for its parts. Although there's a small chance it'll be found, most likely it was chopped up before we realized it was gone. Honestly, it was approaching the age when repairs begin to cost more than a car is worth and we were talking about replacing it. But we would have liked to have done it on our terms.

Other than my hat, not much was in the car. They got Karen's iPod, GPS and favorite sunglasses. Guess what Santa's bringing, honey! We're most unnerved knowing that some dirtbag out there now has our names and address (via the car registration). I unplugged the garage door opener until I can figure out how to reprogram it. We're a little jumpier than usual. Dealing with cops, insurance and rentals disrupts life's pleasant routines.

Mostly we're a little sad. Not deeply sad, as if something had actually died, but it ("she") was the best car we ever owned and we'll miss her. Our family took a lot of trips and lived a lot of life in that car. We never got to say goodbye.

Where's Gil Grissom when you need him?

.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

I'm Supposed to Be Working

I awoke this morning with the word "suppose" rattling around my brain like a wing nut in a tin can. After using it all my life, I just realized what an odd word it is.

"Suppose" can mean something like presume/assume/infer: "I suppose the paint is dry."

It can carry a tinge of resigned acquiesence: "I suppose I'll do the laundry."

Linked with the word "to," it takes on a related but slightly different meaning similar to should: "I'm supposed to pluck the chickens." It's really kind of single thought, isn't it? "Supposedto."

It can also communicate doubt, like alleged: "The supposed psychic Kreskin hypnotized the audience." Sometimes a speaker emphasizes the last syllable to say "suppose-ed" instead of "supposd," but not always. It works either way.

Think about how different a sentence like "I'm supposed to have robbed the bank" is from "I was supposed to rob the bank." Or "I suppose I robbed the bank." Or "Suppose I robbed the bank."

It's a complicated word! Extremely subtle context is key to its meaning. The proper use of "suppose" must be one of the last things a non-native speaker learns. That's Super Advanced English right there, yet most of us get it as children. Language is amazing!

But the big question is this: I'm OK, right? I mean, other people wake up thinking about stuff like this. Sure they do! It's perfectly normal. It's not like I wake up visualizing abstract shapes that I'm compelled to draw over and over in the steamy condensation on the shower door until I've mastered them. That would just be weird.

Right?

.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

One Thing Leads to Another

A six-year update: my girls aren't in high school anymore (whew!) and in fact are both well into earning Masters degrees. As I recall, my talk to their art class went well, though who knows if anything I said stuck. And I believe my conclusion more than ever, enough to consider it one of the fundamental Things I Know Are True. I don't have a lot of those, so you should trust me on this one.

* * *

(December 2005) I've been asked to talk to my girls' high school art class next week. Some of these kids are very talented advanced-placement students already preparing portfolios for future academic and professional careers. I've spoken to high school classes before, usually on the topic of "how I lucked into a career combining two things I love best: science and writing." Now that I've got a published graphic novel in hand, I suppose I can extend that list to include "art," yet I have a nagging fear that some of these kids are already way ahead of me.

I was thinking about what I might discuss when my eyes settled on this laminated card pinned to my bulletin board, my first official press pass:

What a goober.

What a goober.This was where my professional writing career began, fresh out of college at a small daily newspaper in central California. I got the job of part-time night-shift sports writer based on paltry clips of a column I wrote for my college paper plus, I suspect, my ability to type fast--a skill not as common then as it is today. I must have been the only applicant, because anyone else with respiration would've been better qualified. I nevertheless got a foot in the door and covered a season of high school basketball before a full-time (daytime!) position opened on the city beat and I was on my way.

One day the editor bellowed out into the newsroom: did anyone want to fly to Fresno for the weekend to cover the opening of a new power plant? Since no one else spoke up and I was trying to build a reputation as the go-to science guy, I took the assignment. It turned out to be a good story about a hydroelectric turbine complex dug deep inside a mountain between two lakes. The place looked like the subterranean lair of a James Bond villain. I had fun, wrote the feature, and forgot about it.

Helms Pumped Storage Hydro Plant,

Helms Pumped Storage Hydro Plant,

deep underground. I was there once.

Twelve or thirteen years later, after a decade away from journalism, I applied for a position with a small science-writing firm whose clients were mostly in the energy industry. I passed a writing test and showed up for the interview with one relevant clip: the power plant story. I got the job. And thanks to that job, just a couple of years later I was ready to break out on my own and build a self-employed career I've enjoyed ever since.

I derive three lessons from that story for the young'uns. First, take on tasks nobody else wants because someday, somehow, in a way you can't imagine, one of them will pay off.

Second, one thing leads to another in unpredictable ways. Lives have threads and patterns that only reveal themselves in retrospect. In my case, a column in a college newspaper led to part-time sports writing, which led to full-time reporting, which led to freelance magazine writing, which led to something that actually looks like a career in both writing and comics. Pay attention. Be ready for unexpected opportunities.

Third, if you want to be a writer, write. Anything. I learned the most about writing by covering a season of high school basketball. Two or three games are easy; by the tenth or twentieth you're working mightily to keep it interesting for both your readers and yourself. Because, let's face it, every high school ballgame (or city council meeting or planning commission hearing) is pretty much like any other. I figured my job was to pay attention and figure out what made this game, meeting or hearing special, and then explain that. Even if I didn't care about an assignment, it was important to somebody and I had to understand and communicate why. That made me a pro. (My personal definition of "professional" is "doing a good job even when you don't feel like it." Or, as Charles Schulz said, "writer's block is for amateurs.") The same applies to art and comics as well. Just do it.

By the way, in my three years as a reporter and more than ten years as a freelance writer/journalist/editor, I've never once had to show a press pass to anyone. Too bad.

.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Pitching to the Stars

1. My Day Job: multiple year-end deadlines are piling up, and all of my clients believe they are my sole top priority, just as I groomed them to believe. Heh heh heh. Unfortunately, now I have to act like it.

2. Mystery Project X: In any spare time I can find, I am pencilling pages. I thought I'd try something different this time. My plan is to pencil the entire book, then go back and ink it (usually I ink as I go, finishing pages in batches of three or four). I'm hoping it'll produce some stylistic continuity from start to finish, allow me to fold in any great new ideas that come up, and be a bit more efficient. We'll see; I may change my mind. It's all still being done on spec, with no contract or commitment from a publisher (although interest from more than one). I have faith.

3. Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow: With luck, we'll have one or two good things happen in 2012 that I'm working on now and can tell you about later.

Despite my busyness, I still feel a nagging obligation to give you a reason to visit once in a while. So with your indulgence (or without it, just watch me!), from time to time I'll dip into the archives and post a re-run. Since I've been blogging since July 2005, I've got a big backlog of perfectly swell essays little seen or long forgotten. I'll try to pick good ones.

Here, lightly edited, is a post I wrote in September 2006 about something I learned from failing. At the time, Mom's Cancer had been out a few months and I'd just started working on WHTTWOT.

I've written about my great affection and appreciation for the original "Star Trek" before, but in fact my relationship with the series goes a bit beyond that. This is a story I don't tell very often--mostly because it ends in abject failure--but I did talk about it during my 2006 Comic-Con Spotlight Panel and I think it gives some insight into how I approached the writing of Mom's Cancer.

I've written about my great affection and appreciation for the original "Star Trek" before, but in fact my relationship with the series goes a bit beyond that. This is a story I don't tell very often--mostly because it ends in abject failure--but I did talk about it during my 2006 Comic-Con Spotlight Panel and I think it gives some insight into how I approached the writing of Mom's Cancer.The 1960s' "Star Trek" was followed by another series that began in 1987 called "Star Trek: The Next Generation." It ran for seven seasons. I enjoyed the show as a fan, though never as passionately as I did its predecessor, and around the beginning of Season Six I learned that the show would consider scripts from unagented writers. This policy was unique in all of television and the news hit me like a thunderbolt. In a few weeks I came up with a story, figured out proper TV screenplay format, and sent off a full script with the required release forms. Shortly afterward I followed with a second script, the maximum number they allowed.

I don't know how much later--surely months--I arrived home to a message on my answering machine. "Star Trek" wanted to talk to me. Neither of my scripts were good enough to actually shoot, but they showed enough promise that they were willing to hear any other ideas I might have. Would I care to pitch to them?

Yeah. I think so.

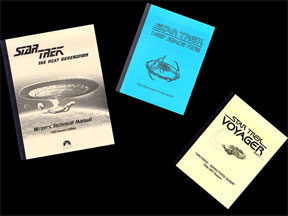

Paramount sent me a three-inch thick packet of sample scripts, writer's guides, director's guides, character profiles, episode synopses: all the background a writer would need to get up to speed (not that I needed them--I'd been up to speed since 1966). I spent several weeks coming up with dozens of ideas, distilled them to the five or six best, and made the long drive to Paramount Studios. Just getting onto the lot was a small comedy of errors: the guard at the gate didn't have my name on the list and I'd neglected to ask which building and office I was supposed to report to. Unlike anyone who's worked in Hollywood in the past 30 years, I wore a tie and sportcoat--a bad idea on a hot day when I was already inclined to sweat prodigiously. But I eventually made my way to the office of producer Rene Echevarria and threw him my first pitch. He stopped me after two sentences.

"We started filming a story just like that last week."

Crap. That was the best one.

Pitches two, three, four and five fared no better. After desperately rifling through my mental filing cabinet for any rejects with a hint of promise, I was done. In and out in less than 30 minutes, weeks of work for naught.

Still, I went home satisfied that I gave it my best shot. I wrote Rene a letter thanking him for the opportunity and expressing a completely baseless hope that he might give me another chance someday.

I got the next call a few weeks later. Rene had gotten my letter, looked over his notes, and decided that, although none of my pitches were good enough to shoot, I merited another shot.

Months later came my second try. By then I was smart enough to spare myself the drive and pitch by phone. If I remember correctly, Rene liked a couple of my stories enough to take them to his bosses, but by this time the series was into its final season and the available episode slots were filling fast. In anticipation of the end of "The Next Generation," Paramount was already producing a successor series, "Deep Space Nine." In my last conversation with Rene, when it was clear "The Next Generation" was done with me, I asked if he could arrange for me to talk to "Deep Space Nine." He was bewildered.

"Why would you want to pitch to those guys?" he asked.

Nevertheless, I soon had an appointment to pitch to those guys, got another thick packet of space station blueprints and character bios, and started writing. I parlayed that opening into several pitches over the show's seven-year run, most to the very professional, generous and kind writer/producer Robert Hewitt Wolfe. And when Paramount started production on the next "Star Trek" series, "Voyager," I tried my old trick on Robert.

"Why would you want to pitch to those guys?" he asked.

So I got more packets of cool stuff, more experience, and more rejection. Although they liked some of my ideas enough to mull them over, I never got close. It was exhausting. At last, after eight or nine years and forty or fifty stories, "Star Trek" and I mutually agreed we'd had enough of each other and parted ways.

Lessons in Writing

Here's my point (and I do usually have one, eventually): even as a complete failure, my experience pitching to "Star Trek" made me a better writer. What I realized was that the stories they quickly rejected focused on some science-fiction high-tech premise or plot twist, while the stories they liked focused on the characters. If I said something like, "Captain Picard starts the story at A, experiences B, and as a result grows to become C," I had their attention. I had to be hit over the head several times to realize that a good story isn't about spaceships or aliens or ripples in the fabric of space-time, but about people.

That sounds blindingly obvious, but I realized how unobvious it was as I talked to friends and family about the experience. As soon as someone hears you have a distant shot at actually writing a "Star Trek" episode, they can't wait to share their ideas with you (never mind how fast they'd sue if you actually used one). And literally without exception, every idea I heard from someone else was about a spaceship, alien, or ripple in the fabric of space-time. Not one that I recall even mentioned a character, how they'd react to the situation, or how they might be changed by it. Once I learned to look for it, it was striking.

These were lessons I internalized as best I could and took into the writing of Mom's Cancer. I realized early that my story couldn't be about the medical nuts and bolts of cancer treatment. First, because there are too many treatment options for anyone to cover; second, because I knew such information would be obsolete very quickly; and third and most importantly, good stories are about people. My book isn't about radiation and chemotherapy and cancer, but about what those things do to a family. If something I scripted or sketched didn't drive my mother's story--if the plot didn't serve the characters--I cut it.

Whatever success my books have had and will have, I think that's the key. With due gratitude to all the Treks.

.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Morning Musing on Deadline

What struck me as odd is that this near-Brian Fies is doing nearly the same job I did when I graduated from college almost 30 years ago: writing about high school girls' sports for a small daily newspaper. His article is about volleyball while I mostly covered basketball, but close enough. In my case, I moved from part-time sports writer to full-time city-beat reporter within a few months, accumulating the writing experience and clips that served me well since. I can't help but wonder if this Bizarro-Fies is duplicating my life, just displaced a couple of decades. What if he looks like a young me? What if he just married a smart and beautiful girl named Karen? I'm tempted to warn him about the twins coming his way in a few years (run, Brian, run!).

I'm reminded of a webcomic by Scott McCloud titled "The Right Number" about a man who misdials his girlfriend's phone number by one digit and calls a woman who is almost exactly like his girlfriend in every respect, except a little better. Maybe this guy is the new, improved Brian 2.0. As long as he isn't required to hunt me down and kill me, we'll co-exist just fine.

Best of luck to you, Brian. I could tell you a few things, but you'll have more fun figuring them out for yourself.

.

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Wimpy Tour

Not that he needs my promotional help, but my pal Jeff Kinney is about to set off on another book tour to mark the release of his sixth "Diary of a Wimpy Kid" book, Cabin Fever. The tour gets underway when the book drops on November 15 with stops in New Jersey, Washington DC, Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia and Florida (the full schedule is here). Befitting this book's theme of being snowed in, I hear that Jeff is bringing along an industrial-strength snow machine to create an instant blizzard wherever he stops. Sounds like fun!

Although Jeff is a friend, I probably wouldn't have mentioned this tour if I didn't have something to say about it (this blog is all about "value added"). First, I understand that the new book will have a first printing of six million copies.

Six million copies.

I said "six million copies."

That's the largest first printing for any book being released in 2011. The first printing of the original Wimpy Kid book was 13,000, and even that is a pretty healthy number in my literary backwater. Six million isn't a number; it's an abstract mathematical construct. If you had a dollar for every book, you could build your own cyborg out of Lee Majors.

In addition, our mutual editor Charlie Kochman is accompanying the tour for the first time. I probably wouldn't have mentioned that either, except I'm hoping someone will read this, go to one of Jeff's signings, recognize Charlie, say "Hi, Editor Charlie!" and totally blow his mind. Should you accept the assignment, this is your target:

If you want to attend one of these signings/hypothermiafests, I'd advise you to check with the hosting bookstore to see what sort of procedure or ticket is required and arrive very early. Thousands of squealing kids will turn out for these things. A couple of years ago I visited Jeff at one of his appearances in my part of the country, and it was pretty surreal--as I wrote at the time, probably as close as I will ever get to being a roadie for The Beatles. Luckily, Jeff is talented and nice enough that he deserves it. I know how hard he works on these books and look forward to reading his latest.

.