The Last Mechanical Monster. A Fire Story. Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow? Mom's Cancer.

Friday, December 30, 2016

Blue Highways

I'm reading Blue Highways, a gift from my friend Marion, in a way author William Least Heat-Moon never intended and probably couldn't have foreseen. Blue Highways is Heat-Moon's travelogue of his three-month loop through the backroads--the map's blue highways--of the United States in 1978. It was a bestseller at the time, and a book I always knew about and wanted to read but never quite got to. Now I have.

Blue Highways is partly an elegy to a then-vanishing America, where people lived as they had fifty years before. Heat-Moon didn't have to wander far off the interstate to find folks living in tarpaper shacks with no plumbing, drinking free spring water that bubbled up from half a mile underground and eating whatever they could catch from the local pond. The book has one foot in the then-now and another in the past.

Reading it today, nearly forty years after Heat-Moon's odyssey, piles another time shift on top. Now I can follow his route on Google Maps, and use Street View to tour the towns he traveled through. I can Google the businesses he patronized and the people he met. Some of them turn up. Heat-Moon didn't know how all the stories he told would turn out; now, I can look up the endings of at least a few.

Not surprisingly, most of Heat-Moon's America from fifty-years-before-1978 appears to be gone. A little more surprisingly, so does a lot of his America from 1978. It wasn't that long ago. I was there. Blue Highways did (unintended?) double duty, documenting both its past and its present before they both passed into its future--where I can ride along with Heat-Moon on a computer that's about the same size and weight as the paperback edition I'm reading.

It's a trip.

Saturday, December 24, 2016

Pogo & His Pals

Golly, I haven't blogged in a couple of months. I may have run out of things to say, or outgrown the conceit that anyone cares. My intentions are good. Maybe next year.

However, I can't let this year pass without posting a bit of whimsy that's been a tradition on my blog every Christmas Eve since way back in aught-five: "Pogo" cartoonist Walt Kelly's timeless carol, "Deck Us All With Boston Charlie." You know the tune. After that, for the first time ever, I've added a bonus cartoon by "Polly and Her Pals" cartoonist Cliff Sterrett, who in my opinion is the greatest underappreciated cartoonist you've never heard of from the first half of the 20th Century. I love Sterrett. This'll suggest why.

All my best for today, tomorrow, and the New Year. Thanks for reading.

Brian

However, I can't let this year pass without posting a bit of whimsy that's been a tradition on my blog every Christmas Eve since way back in aught-five: "Pogo" cartoonist Walt Kelly's timeless carol, "Deck Us All With Boston Charlie." You know the tune. After that, for the first time ever, I've added a bonus cartoon by "Polly and Her Pals" cartoonist Cliff Sterrett, who in my opinion is the greatest underappreciated cartoonist you've never heard of from the first half of the 20th Century. I love Sterrett. This'll suggest why.

All my best for today, tomorrow, and the New Year. Thanks for reading.

Brian

Deck us all with Boston Charlie,

Walla Walla, Wash., an' Kalamazoo!

Nora's freezin' on the trolley,

Swaller dollar cauliflower alley-garoo!

Don't we know archaic barrel,

Lullaby Lilla boy, Louisville Lou?

Lullaby Lilla boy, Louisville Lou?

Trolley Molly don't love Harold,

Boola boola Pensacoola hullabaloo!

Bark us all bow-wows of folly,

Bark us all bow-wows of folly,Polly wolly cracker n' too-da-loo!

Hunky Dory's pop is lolly

gaggin' on the wagon,

Willy, folly go through!

Donkey Bonny brays a carol,

Antelope Cantaloup, 'lope with you!

Chollie's collie barks at Barrow,

Harum scarum five alarum bung-a-loo!

Antelope Cantaloup, 'lope with you!

Chollie's collie barks at Barrow,

Harum scarum five alarum bung-a-loo!

Wednesday, September 28, 2016

My Fellow Super-Americans

The "What Would Clark Kent Do?" filter works surprisingly well. Here's a partial list of things I'm pretty sure he wouldn't do:

Make fun of fat women.

Make fun of ugly women.

Make fun of menstruation.

Make fun of the disabled.

Insult POWs.

Insult the parents of dead soldiers.

Extort his allies ("Eh, nice country you got here, be a shame if somethin' happened to it.")

Go into business with General Zod.

Praise the way General Zod handles the press and dissidents.

Suggest that General Zod could maybe help him get rid of his enemies.

Lie; then when confronted with that lie, double down or deny.

Brag.

Bluster.

Bully.

When caught bullying, retort "Can't you take a joke?"

Blame his failures on everyone but himself.

Appeal to people's worst instincts instead of their best.

Really, the list is practically endless. I keep waiting for a modern-day Joseph Welch versus Joe McCarthy moment, but I'm not sure we have it in us anymore. Decency is too old-fashioned.

I don't expect to change anyone's mind, and I'm breaking my rule about not doing politics online. Might regret it; don't care. I had to stand up and be counted. Clark would.

Here's the above comic laid out in two pages, which I wasn't sure would be readable at blog size. Click to embiggen. Thanks for your indulgence.

Tuesday, September 6, 2016

The Grand Delusion

Over the weekend, Karen and I saw and really enjoyed "Florence Foster Jenkins." Based on an actual woman who's been called the World's Worst Singer, the film stars Meryl Streep, who may deserve an Oscar for her performance as Florence; Hugh Grant, who Hugh-Grants his way through a good performance as Florence's morally ambiguous husband (I think the film answers the question of whether he truly loves Florence but you may disagree); and Simon Helberg, "The Big Bang Theory's" Wolowitz, who gives a master class in reactive acting as Florence's horrified new accompanist.

Madame Florence was a wealthy woman in pre-War New York City whose patronage of the musical arts made her a pillar of high society. But merely supporting the arts wasn't enough for her. She wanted to sing, first at exclusive performances at the Verdi Club she founded to showcase her talents, then eventually at Carnegie Hall.

No one ever doubted Madame Florence's passion for music, just her ability to do it. She became a hit by being terrible, and according to the film and some profiles I've read, most people played along, complimenting and applauding as if she were terrific. Cole Porter and Enrico Caruso were fans. There's debate about how self-aware Florence was. Streep plays her as completely deluded and clueless until she gets an honest devastating review; some contemporaries said she was in on the joke.

I thought the movie was very good and, like all good movies, inspired a lot of thinking as I left the theater. For example, about Emperor Norton.

Norton the First, Pepper the Last

Joshua Norton arrived in San Francisco in 1849, and ten years later proclaimed himself "Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico." He ordered the U.S. Army to disband Congress, and commanded that a suspension bridge be built between San Francisco and Oakland. He may have also imposed a $25 fine on anyone caught using the word "Frisco."

|

| Norton I |

Norton wore a flashy uniform given to him by Army officers at the Presidio. When that uniform wore out, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors requisitioned him a new one. Penniless, he printed his own currency, which was accepted by restaurants and merchants. Passersby bowed to him. Theaters left a balcony seat open for him. He once broke up an anti-Chinese-immigrant riot by standing between two mobs and reciting The Lord's Prayer.

Norton was arrested once, in 1867, by a cop who thought he was insane and ought to be committed. Citizens and newspapers rose up in outrage. The Daily Alta editorialized that the Emperor "has never shed blood, has robbed no one, and despoiled no country...which is a hell of a lot more than can be said for anyone else in the king line." The police chief released him with a formal apology, and afterward police officers saluted Norton whenever they passed him on the street.

Norton died in 1880, as beloved an emperor as the United States and Mexico ever had. His suspension bridge between San Francisco and Oakland was eventually built in 1936. Although it's called the Bay Bridge, there is still today a popular campaign to rechristen it the Emperor Norton Bridge.

This train of thought, from Madame Florence to Emperor Norton, inevitably brought me around to Pepper.

|

| Pepper |

I often saw Pepper around town but only had one direct run-in with her. I was probably 17 or 18, coming out of a store and heading to my car in the parking lot, when Pepper accosted me. "I need to go north. Which way are you going?" I was in fact headed north, but not wanting to provide a taxi that day, I stammered out, "Uh...south. Downtown." "That's exactly where I'm going too!" she said brightly. "Let's go!" Three miles later, I dropped her off downtown and turned around, completely outmaneuvered by the town marshal.

Pepper died in 1992, complaining that people weren't as friendly as they used to be. She was right. Do we have a Florence Foster Jenkins, Emperor Norton, or Pepper anymore? Could we? Should we?

There's some condescension in playing along, smirking knowingly behind their backs. Some might say we're not doing the deluded any favors by indulging them. But, as the Daily Alta argued, if they're not hurting anyone then what's the harm? Who's to say a little collective compassionate fantasy isn't better than harsh reality? Would you tell Madame Florence she couldn't sing, tell Norton the First he wasn't emperor of anything, tell Pepper she had no authority to harass jaywalkers?

I wouldn't have the heart.

Here's Where I Stretch the Theme Too Far

Sometimes when striving writers and artists are being deep and honest, they ask each other how they're supposed to tell whether they're any good. How do you know if you're truly talented and ought to keep trying until you get one good break, or if you're a tone-deaf Florence Foster Jenkins? Winners never quit, but neither do a lot of folks who really should.

Sometimes they ask me what I think. It's a very tough question. I don't trust my own judgment enough to flat out tell anyone to quit and go home. I'm not in the spirit-crushing business. Besides, lots of people whose careers completely mystify me are doing a lot better than I am. What do I know?

I wouldn't have the heart.

I try to read the audience. Nine out of ten people who say "Don't be afraid to tell me what you really think" don't want to know what you really think. They just want to hear that they're great. Anything less than that and their defenses go up and their excuses come out. The other one out of ten is genuinely interested in feedback and trying to learn from it. I think of them as the pros, even if they've never sold anything (yet). It's not necessarily related to age or experience. I've seen 15-year-olds take constructive criticism better than 35-year-olds.

The best advice I've come up with (and I don't think it's great) is to look for external signs of progress. "External" means someone other than your mom or spouse or best friend telling you you're a genius. Someone like an editor. Notice I'm not saying "money," although getting paid is the only sure-fire unambiguous compliment. But if you're doing your best work and getting it in front of people who have the potential to someday pay for it, I have some faith that if you're any good they'll eventually notice. Maybe a note of encouragement along with the customary rejection, or a suggestion for something different you might try next time. Build on that.

Try not to be Florence Foster Jenkins.

Monday, August 15, 2016

Mark Twain Insult of the Day #15

From Volume 3 of the Autobiography of Mark Twain, today's subject: Lilian Aldrich, the wife of writer and Clemens acquaintance Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

"A strange and vanity-devoured, detestable woman! I do not believe I could ever learn to like her except on a raft at sea with no other provisions in sight."

"A strange and vanity-devoured, detestable woman! I do not believe I could ever learn to like her except on a raft at sea with no other provisions in sight."

Thursday, July 28, 2016

Richard Thompson

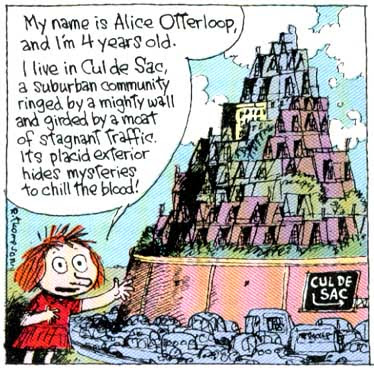

Cartoonist Richard Thompson died yesterday from Parkinson's disease at age 58. Michael Cavna wrote a good obit in the Washington Post, for which Richard did a lot of work. Richard was also the genius behind the comic strip Cul de Sac, which, when it retired in 2012 because Parkinson's had made it too difficult for Richard to draw, I called the best comic strip of the 21st Century. So far, it still is.

Unlike most people, I don't throw around the word "genius" lightly. To me it means something beyond "extremely smart and talented." More like "sprung full-blown from the brow of Zeus," doing things I don't even understand how any human could do. Richard did that.

The past couple of weeks I've been writing the Comic Strip of the Day blog while its founder, Mike Peterson, recovered from surgery. Mike came back yesterday, and for my final two posts on Monday and Tuesday I republished the testimonial I posted here when Cul de Sac closed up shop. I won't re-repost it again, but here's Part 1 and Part 2. Richard died on Wednesday.

The timing was coincidental but providential. I'd heard from people close to Richard that he was in very bad shape but didn't know he was near death. I reposted that piece partly because I wanted people to think good thoughts about him, and hoped he might see it and it would make him happy. Monday's Part 1 post got a Facebook "Like" in his name. He obviously didn't push the button but someone near him did, so I'm grateful for that.

I never met Richard but we exchanged some messages over the years. He was the same with me as he was with everyone: kind, funny, generous with his time and praise. I live 3000 miles away but always hoped I'd have a chance to take him up on the cup of coffee he promised, and I don't even drink coffee. I'm pretty heartsick and gutted by his loss.

Chris Sparks started Team Cul de Sac to raise money for Parkinson's disease research in Richard's name. I contributed a drawing to a tribute book published a couple of years ago, and the group is still active at comics conventions and online, doing good work with the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Check them out.

I recommend two good books: The Complete Cul de Sac, which collects all of the strips in Cul de Sac's five-year run, and the Art of Richard Thompson, which, if you're an artist, will either inspire you to work harder or give up.

In addition, Picture This Press will soon release two books as part of its Richard Thompson Library: The Incompleat Art of Why Things Are, collecting Richard's illustrations for Joel Achenbach's column in the Washington Post, and Compleating Cul de Sac.

If you're curious what a genius looks like, watch this video. I'll miss having him in the world.

Monday, July 11, 2016

Comic Strip of the Day

My friend Mike Peterson runs a fine blog called Comic Strip of the Day (CSOTD), which does what its title says. Every day Mike reads a couple hundred comics and picks out those that inspire an essay or provide an interesting juxtaposition. He's a very good writer and it's a daily stop of mine.

When I heard Mike would be going into the shop for a tune-up, I offered to take over CSOTD while he recovers. I made it sound like I was doing him a favor, when in fact he's doing me one: I love comics, I love to write, and I like the discipline of having to produce something daily on deadline. This'll be fun.

Also, when you get a bunch of readers in the habit of checking in with you every day, never give them an excuse to get away. I'm hoping Mike's readers will stick with CSOTD while I fill in. Maybe I can even convince someone who knows me but doesn't know Mike to start reading CSOTD. That'd be cool.

My first CSOTD is Tuesday, July 12. Mike has already linked to this blog and I'll cite it a few times myself, so by way of introduction: I'm a writer, journalist, cartoonist, and creator of comics you can learn more about by clicking those links to the right. Further down are eight years (!) of my blog archives.

I'm doing CSOTD my way, not Mike's, and Mike's OK with that. Mike's Prime Directive is that he never singles out comics for snark and abuse. It's also mine. I'll be less political than Mike. I don't do politics online; in my experience it just makes people mad and never changes anybody's mind. I also don't think I'll have time to read a couple hundred comic strips per day. But I hope to have interesting things to say about comics, and I have some surprises planned.

I have no idea how long I'll be guest-hosting while Mike recuperates. Probably between two and six weeks. I think Mike's tough and stubborn enough to hit the low end of that range.

I'll leave the lights on for you, Mike.

When I heard Mike would be going into the shop for a tune-up, I offered to take over CSOTD while he recovers. I made it sound like I was doing him a favor, when in fact he's doing me one: I love comics, I love to write, and I like the discipline of having to produce something daily on deadline. This'll be fun.

Also, when you get a bunch of readers in the habit of checking in with you every day, never give them an excuse to get away. I'm hoping Mike's readers will stick with CSOTD while I fill in. Maybe I can even convince someone who knows me but doesn't know Mike to start reading CSOTD. That'd be cool.

My first CSOTD is Tuesday, July 12. Mike has already linked to this blog and I'll cite it a few times myself, so by way of introduction: I'm a writer, journalist, cartoonist, and creator of comics you can learn more about by clicking those links to the right. Further down are eight years (!) of my blog archives.

I'm doing CSOTD my way, not Mike's, and Mike's OK with that. Mike's Prime Directive is that he never singles out comics for snark and abuse. It's also mine. I'll be less political than Mike. I don't do politics online; in my experience it just makes people mad and never changes anybody's mind. I also don't think I'll have time to read a couple hundred comic strips per day. But I hope to have interesting things to say about comics, and I have some surprises planned.

I have no idea how long I'll be guest-hosting while Mike recuperates. Probably between two and six weeks. I think Mike's tough and stubborn enough to hit the low end of that range.

I'll leave the lights on for you, Mike.

Sunday, July 3, 2016

$87.68

My friend Marion is a writer whose recent blog post with that same title got me thinking. Marion recently retired and is pursuing her avocation of writing with every hope of making it a vocation (I assume; I've never really asked her, but I figure she wouldn't mind making some money at it). $87.68 is the sum she earned for selling a science fiction story, and the pride she took in depositing that check was hugely out of proportion to its dollar value.

I'm thrilled for her.

Marion's post is about the disappointment and hurdles writers face, the "locked doors, barred windows and Don’t Even Think of Parking Here signs you see in the writing biz, long before you even get a rejection." I think it's a good essay that's worth reading, but the bit that got my attention talks about the discouragement she especially feels from other writers.

"There are so many, and they are so consistent in their urge to explain that writing is hard work, that you aren’t a special snowflake and your words really don’t matter, that publishing is a cutthroat business run by shoemakers who don’t care about books and you can’t trust anyone, that I do have to wonder if some of it isn’t motivated, if unconsciously, by a desire to thin out the competition. And it will work, if you let it, because the chorus is so constant."

That hit hard because I think I've been that guy, though not to Marion I hope. I've told people that writing is hard work, getting published is difficult, there is a lot of competition, much relies on luck, and publishing is run by shoemakers who are more concerned with markets and dollars than art and literature because if they weren't, they wouldn't stay in business.

Problem is, I think that's all true.

In my mind, I'm trying to honestly share a few things that surprised me or I learned the hard way. I don't think blind encouragement is useful. "Winners never quit and quitters never win" can do a lot of harm to people who really should quit and find something else that makes them happy. Clear-eyed perspective is good. I'm trying to help.

Marion's got me wondering if I'm doing it wrong.

The more I trundle along my own semi-literary semi-career, the more I'm convinced that nobody knows nuthin'. Everybody I know who's "made it" has a different story about how they did it, and their method probably won't work for you. The only way knowing my story would help you is if you had a time machine to travel back to 1983 and beat me out for a part-time night-shift sportswriting job at a small daily newspaper, because that's how I first got paid to write and you surely would have been more qualified than I was.

Otherwise, sorry. You're on your own.

Shortly after Mom's Cancer was published and had gotten some attention, my editor asked me to meet with a new writer whose first book was about to come out, and give him the straight dope. Writer to writer, heart to heart. We met at the San Diego Comic-Con, and because we couldn't find any chairs we sat on the floor of the mezzanine, between the snack bar and the Klingons.

"Getting a book published is cool, and you're going to meet some nice and interesting people," I said. "Enjoy it. But don't quit your day job. The money truck is not going to back up to your door. This is not going to change your life." I summed up my publishing experience as a mixture of profound satisfaction tinged with vague disappointment.

You've guessed the punchline. That guy was Jeff Kinney, creator of Diary of a Wimpy Kid, whose series now has about 180 million books in print and two motion pictures to its credit.

Jeff still remembers our conversation. We laugh and laugh. Sometimes I can hear the gold coins jingling in the background as he backstrokes through his Scrooge McDuck money vault.

My point is, I have proof I'm breathtakingly bad at giving professional advice.

Marion says it can seem like writers talk tough to cut down on competition. I understand her perspective but I've never seen it. Usually the opposite; I find writers are very generous with their time, tips and advice. Some are grumpy misanthropes, but more than you'd expect love to talk shop, gossip about agents and editors, and welcome newbies as peers. Sometimes you can't shut them up. Most of them remember what it was like and don't mind lending a hand if they can.

It can seem like people ahead of you in the race throw hurdles in your way to stop you, when really those hurdles are just things you need to learn and put behind you, then look back and wonder how they ever slowed you down.

I'll take every opportunity to reprint Mark Twain's advice to writers: "Write without pay until somebody offers pay. If nobody offers pay within three years, the candidate may look upon this circumstance with the most implicit confidence as the sign that sawing wood is what he was intended for."

Writer Mark Evanier, whose "News from ME" blog is a daily stop of mine, just posted the 13th installment of a possibly-never-ending series he's writing on the topic of Rejection (that post includes links to the previous 12; I'm partial to Part 6 myself, try that one first). If you're wondering why nobody buys your stuff and you can't catch a break and the rules seem stacked against you, Mark has some good insight.

I don't. Marion's post, and my demonstrated history of giving spectacularly wrong advice, remind me that humility is in order. I think I could strike a better balance between encouragement and discouragement. I'll try.

Do your best work. Get it out into the world however you can. Then do better work. I don't know much but I'm pretty sure that's right.

Good luck! You'll need it.

Rats! I blew it already.

I'm thrilled for her.

Marion's post is about the disappointment and hurdles writers face, the "locked doors, barred windows and Don’t Even Think of Parking Here signs you see in the writing biz, long before you even get a rejection." I think it's a good essay that's worth reading, but the bit that got my attention talks about the discouragement she especially feels from other writers.

"There are so many, and they are so consistent in their urge to explain that writing is hard work, that you aren’t a special snowflake and your words really don’t matter, that publishing is a cutthroat business run by shoemakers who don’t care about books and you can’t trust anyone, that I do have to wonder if some of it isn’t motivated, if unconsciously, by a desire to thin out the competition. And it will work, if you let it, because the chorus is so constant."

That hit hard because I think I've been that guy, though not to Marion I hope. I've told people that writing is hard work, getting published is difficult, there is a lot of competition, much relies on luck, and publishing is run by shoemakers who are more concerned with markets and dollars than art and literature because if they weren't, they wouldn't stay in business.

Problem is, I think that's all true.

In my mind, I'm trying to honestly share a few things that surprised me or I learned the hard way. I don't think blind encouragement is useful. "Winners never quit and quitters never win" can do a lot of harm to people who really should quit and find something else that makes them happy. Clear-eyed perspective is good. I'm trying to help.

Marion's got me wondering if I'm doing it wrong.

The more I trundle along my own semi-literary semi-career, the more I'm convinced that nobody knows nuthin'. Everybody I know who's "made it" has a different story about how they did it, and their method probably won't work for you. The only way knowing my story would help you is if you had a time machine to travel back to 1983 and beat me out for a part-time night-shift sportswriting job at a small daily newspaper, because that's how I first got paid to write and you surely would have been more qualified than I was.

Otherwise, sorry. You're on your own.

Shortly after Mom's Cancer was published and had gotten some attention, my editor asked me to meet with a new writer whose first book was about to come out, and give him the straight dope. Writer to writer, heart to heart. We met at the San Diego Comic-Con, and because we couldn't find any chairs we sat on the floor of the mezzanine, between the snack bar and the Klingons.

"Getting a book published is cool, and you're going to meet some nice and interesting people," I said. "Enjoy it. But don't quit your day job. The money truck is not going to back up to your door. This is not going to change your life." I summed up my publishing experience as a mixture of profound satisfaction tinged with vague disappointment.

You've guessed the punchline. That guy was Jeff Kinney, creator of Diary of a Wimpy Kid, whose series now has about 180 million books in print and two motion pictures to its credit.

Jeff still remembers our conversation. We laugh and laugh. Sometimes I can hear the gold coins jingling in the background as he backstrokes through his Scrooge McDuck money vault.

My point is, I have proof I'm breathtakingly bad at giving professional advice.

Marion says it can seem like writers talk tough to cut down on competition. I understand her perspective but I've never seen it. Usually the opposite; I find writers are very generous with their time, tips and advice. Some are grumpy misanthropes, but more than you'd expect love to talk shop, gossip about agents and editors, and welcome newbies as peers. Sometimes you can't shut them up. Most of them remember what it was like and don't mind lending a hand if they can.

It can seem like people ahead of you in the race throw hurdles in your way to stop you, when really those hurdles are just things you need to learn and put behind you, then look back and wonder how they ever slowed you down.

I'll take every opportunity to reprint Mark Twain's advice to writers: "Write without pay until somebody offers pay. If nobody offers pay within three years, the candidate may look upon this circumstance with the most implicit confidence as the sign that sawing wood is what he was intended for."

Writer Mark Evanier, whose "News from ME" blog is a daily stop of mine, just posted the 13th installment of a possibly-never-ending series he's writing on the topic of Rejection (that post includes links to the previous 12; I'm partial to Part 6 myself, try that one first). If you're wondering why nobody buys your stuff and you can't catch a break and the rules seem stacked against you, Mark has some good insight.

I don't. Marion's post, and my demonstrated history of giving spectacularly wrong advice, remind me that humility is in order. I think I could strike a better balance between encouragement and discouragement. I'll try.

Do your best work. Get it out into the world however you can. Then do better work. I don't know much but I'm pretty sure that's right.

Good luck! You'll need it.

Rats! I blew it already.

Tuesday, June 14, 2016

Assitude: Mark Twain Insult of the Day #14

|

| Queen Anne's Mansions, 1905 |

See the previous post for context for this series of posts excerpting colorful insults from Mark Twain's autobiography . . .

Today's target of Twain's ire is the proprietor of a block of luxury flats in London called Queen Anne's Mansions, where Sam Clemens and his family stayed during an extended visit in 1899. Mrs. Clemens needed to do some shopping, so Clemens tried to cash the equivalent of a Traveler's Check called a "circular check" at the front desk:

"I sent down a circular check to the office to be cashed--a check good for its face in any part of the world, as any ordinary ass would know--but the ass who was assifying for the Queen Anne Mansions on salary didn't know it; indeed I think that his assitude transcended any assfulness I have ever met in this world or elsewhere.

. . . It was strange--it has always seemed strange, to me--that I did not burn the Queen Anne Mansions."

Sunday, June 12, 2016

Twain, Mark III

I'm reading the third volume of Mark Twain's autobiography, which I wouldn't recommend to anyone but am enjoying immensely.

That's not necessarily a contradiction.

The first volume, published 100 years after Sam Clemens's death per the terms of his will, was a surprise bestseller. I found mine on a pallet at Costco. But I suspect that book's ratio of "Copies Sold vs. Copies Actually Read" rivaled those of Stephen Hawking's Brief History of Time and Allan Bloom's Closing of the American Mind. Volumes 2 and 3 did not follow Volume 1 onto the bestseller list. Friends told me they couldn't get through 20 pages of it.

I sympathize. It's tough sledding on a dry hill, especially the early chapters which are organized to satisfy completist academics but frustrate casual readers. I've found the whole thing (a couple thousand pages worth) delightful and rewarding but wouldn't push it onto anyone.

Twain rejected the idea of writing a typical chronological autobiography. Instead, he dictated whatever was on his mind that particular day over the course of several years, reasoning that was the best way to really understand a person's thinking and life. Sometimes a day's entry took him back to his childhood in Hannibal or his early writing career in California. Just as likely, he'd spin off of something he'd read in that day's newspaper. Each two- or three-page bite feels like a one-way conversation sitting at Clemens's side. The upside is tremendous immediacy. You Are There, witnessing history. The downside, I think, is lack of depth, organization, and introspection. Clemens, for all his wit and self-awareness (he gleefully admits to basking in his reputation as a great man of letters), wasn't his own best analyst.

The beauty of the autobiography is that Clemens was aware of that, too, which was another rationale for writing it as he did. He realized that baring his thoughts nearly free-association style would reveal more about him to readers than even he knew himself. I think he was right.

Which is all prelude to this: In my long-ago days of reading Volumes 1 and 2, I posted irregular excerpts under the heading "Mark Twain Insult of the Day." Of all Clemens's writing, I think I love his insults the most. They're vivid, incisive, and paint perfect little portraits that sound like people we all actually know. Today's involves a British novelist named Marie Corelli, a casual acquaintance who, in this episode, roped Clemens into accepting a lunch invitation against his better judgment. Clemens didn't like Corelli. At all.

Mark Twain Insult of the Day #13

"I think there is no criminal in any jail with a heart so unmalleable, so unmeltable, so unphazeable, so flinty, so uncompromisingly hard as Marie Corelli's. I think one could hit it with a steel and draw a spark from it.

"She is about fifty years old, but has no gray hairs; she is fat and shapeless; she has a gross animal face; she dresses for sixteen, and awkwardly and unsuccessfully and pathetically imitates the innocent graces and witcheries of that dearest and sweetest of all ages; and so her exterior matches her interior and harmonizes with it, with the result--as I think--that she is the most offensive sham, inside and out, that misrepresents and satirizes the human race today."

|

| Marie Corelli. She doesn't look so awful. |

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

Mom's Cancer at GoComics.com

After more than a year, Mom's Cancer is near wrapping up on GoComics.com.

What the what?

I haven't exactly trumpeted it from the towers, but Universal Press, the comic strip syndicate that runs GoComics, has been posting two pages of Mom's Cancer per week online since April 2015. Readers can drop in casually or subscribe to as many comic strips as they want. Mom's Cancer has 858 subscribers, which is a comparatively small number (some GoComics strips have tens of thousands). The way I look at it, that's 858 more readers than I had before, plus an unknown number of readers who aren't subscribers.

The last page of the comic, above, ran last Monday. That'll be followed by four strips reprinting the Afterword that Mom herself wrote for the book--in my opinion, the best part of the whole deal--and one strip updating events.

Mom's Cancer got online after I was contacted by Universal editor John Glynn asking if I were interested. That right there is pretty cool. John is one of the comics business's key gatekeepers, and the fact that he knew my book and wanted it on his site was very flattering. John didn't know I'd been pestering my publisher, Abrams, to let me put Mom's Cancer back online where it began as a webcomic. Sales of the print book have been on the long tail of their natural bell curve for a long time, so I saw no harm and much potential benefit. Surely some new readers who discovered it online would want to buy the book. I put Universal's people together with Abrams's people and, months (and months) later, Mom's Cancer was back on the web.

It's been an interesting experience.

First, the story reads very differently serialized twice per week. The pace is different, which affects the readers' experience. I think it actually changes the story in subtle ways (as did its transformation from webcomic to book). Some good, some bad.

Second, GoComics readers--by which I mean those who leave comments on the pages--were a new experience for me. There are maybe half a dozen regulars whose notes I'm always happy to see. Some readers tried the strip and said it was just too painful to read. Understood. There've also been a few oddballs.

Especially in the early days, a lot of readers suggested different cancer treatments and cures we should try, unaware that the story happened 10 years ago. (To be fair, I didn't trumpet that fact either.) Well-meaning people sending their best wishes for Mom's good health broke my heart a little. In the whole year-plus I only deleted one comment--it was pushing a snake-oil miracle cancer cure--which I think speaks well for Internet civility.

It's been weird for me to read Mom's Cancer fresh. It'd been a long time since I actually sat down and read it, and it dredged up some incidents and emotions I would have otherwise forgotten. "Oh yeah, that happened. Yikes!" With some distance, although I'd do some things differently today, I immodestly think it's still pretty good and I'm proud of it.

I appreciate John Glynn and Abrams giving me this new opportunity to share it, and I especially appreciate the new readers who tried it and stuck with it.

Monday, May 16, 2016

Darwyn Cooke

Comic book creator Darwyn Cooke died last week at the too-young age of 53. Cancer. Friends of his in and out of the industry are mourning his death, talking about what a good person he was: enthusiastic about his work, generous with his time, friendly to fans, making comics for the right reasons.

I can't talk about that because I never met him. I just loved his work. So I'll talk about that.

|

| There are a hundred stories in the city, and Cooke tells all of 'em in one drawing. |

Understand that everything below this sentence is my opinion based on a lifetime reading, studying and creating comics. This is what I see when I look at Cooke's work. If you see something else, that's good too.

Cooke came to comics from animation, and it shows. Animation is all about economy: draw nothing but the lines you absolutely must, because you'll be drawing them another 10,000 times. Character designs are often based on simple geometric shapes that are easy to turn in space as the character moves. Clean lines, solid blacks. Not a lot of fussing around.

|

| A tradition of animation excellence echoed in Cooke's art: Superman by the Fleischer brothers, Space Ghost model sheet by Alex Toth, Jonny Quest model sheet by Doug Wildey. The Fleischer Superman cartoon shorts are particularly beautiful examples that influenced generations of creators including Cooke and me, as in my "Last Mechanical Monster" webcomic. |

Cooke built on his animation roots and transcended them. His style is often called "retro," and I'm sure some of that was due to Cooke looking back at the Old Masters of the 1940s and '50s, liking what he saw, and incorporating some of their look and feel. But I'll bet a lot of it involved Cooke facing the same storytelling problems they did and arriving at similar solutions on his own. Because while Cooke does evoke the past, nobody in any decade drew like he did.

Illustrators vs. Essentialists

There are two approaches to cartooning I'll call the Illustrators and the Essentialists. Scott McCloud probably has other names for them but that's how I think of them. Those aren't the only two approaches--there are others that could be called Abstract, Impressionism, Photorealism, etc., roughly corresponding to the same schools in fine art--but they're the two that I think illuminate Cooke's unique talent.

Illustrators have a long pedigree, coming out of the tradition of book illustration that predated comic strips and comic books. It's tempting to call it a "realistic" style, but there's nothing really realistic about it. It's romantic, heroic, detailed, dynamic. Classical. This is the kind of art most people think of when they think "comic books." It's also the type of art that anyone can look at and think, "Wow, that's good drawing!"

The artists I'm calling Essentialists take a different approach. The idea is that comics shouldn't necessarily try to mimic reality but instead embrace their built-in comic-ness. The ideal comic is one that distills reality to its essence, omitting anything that doesn't matter. Simplify, polish, pare. This approach is common among some types of comics--Charlie Brown's face is a masterpiece of minimalism--but unusual in superhero comics.

|

| Two dots, a half circle and a squiggly line are all Charles Schulz needed to create a character who could break your heart. |

Cooke stood out because he was an Essentialist in an industry filled with Illustrators. Here's an example. On the left, Batman by Neal Adams; on the right, Batman by Darwyn Cooke. Adams drew hundreds of lines defining the contours and expression of Batman's face. Cooke drew two, plus two white triangles for eyes. You couldn't draw much less than that, yet it's still instantly recognizable as Batman.

|

| Compare how the artists handled the shading on Batman's forehead. Adams's is all elaborate cross-hatching and feathering, while Cooke's is a simple swath of black. |

I'm not criticizing Adams! He's one of the all-time greats. They were different artists pulling from different traditions to different ends. But the graphic clarity and immediate punch of Cooke's style is very strong and appealing.

One reason Cooke's work struck me as powerfully as it did is because I'm an Essentialist, too. Whenever I redraw something, it's always to take out lines, never to add them. My perfect comic would be a single line that conveys exactly the information or emotion I intend.

It takes a lot of hard work to make it look easy.

Which isn't to say that Cooke's drawings were simple. Not at all. They were often filled with action and detail, but they were always clear and uncluttered. Cooke's gracefully balanced compositions guided the reader's eye where he wanted it to go. Not a line was wasted.

|

| (EDITED TO ADD: This is irrelevant but kind of cool: out of curiosity, I looked up this location in Google Street View and found the sign. How about that!) |

Inkiness

The panel immediately above, from Cooke's adaptation of Richard Stark's Parker novels, shows one way in which Cooke outgrew his animation foundation: brushwork. I don't know enough about Cooke's methods to know if he used actual brushes to put ink on paper, or electronic styluses to put pixels on monitors, but it hardly matters. The controlled looseness of his ink line (or virtual ink line?) wouldn't work for animation but fits right into one of comics' oldest and finest traditions.

|

| Masterful brushwork by Milton Caniff (top), Will Eisner (center) and Mort Meskin (bottom). |

The casual confidence required to command line, form, light and shadow with such apparent ease astonishes me. Bringing a line to life is one of the hardest artistic feats there is. I feel like I pull it off maybe one out of every thirty or forty tries. Cooke managed to do it every time.

Proportions

Cooke also did a subtle thing that humanized his characters and separated him from the pack: he (mostly) drew them in realistic proportions.

Since the ancient Greeks, artists have known that if you want to make someone look really heroic, give them a disproportionately small head (or, if you prefer, a disproportionately large body). Most real-life adults are about 7½ heads tall; most superheroes are at least 8 heads tall. Sometimes 9 or 10 or more.

|

| This ancient Greek statue of the god Apollo has about the same proportions as the Superman drawing above. |

|

| This Hulk is so incredibly powerful that his fists are twice as large as his puny head! And those feet! Yikes! |

Heroic proportions can get pretty ridiculous once you start noticing them. For the most part, Cooke reined his in. This created an interesting paradox: despite how abstract and stylized he drew his characters, they often looked more real than characters drawn in a more detailed illustrative style.

|

| Wonder Woman and Batman, in atypically realistic proportions. |

Cooke's men have barrel chests but aren't muscle-bound. His women have broad shoulders and credible waists. His characters are thick and powerful. They have weight. To me they suggest circus performers in costumes--which were Siegel and Shuster's inspiration when they created Superman.

Color

Again, I don't know enough about Cooke's working method to say how his art was colored. I don't want to give him too much or too little credit. Coloring isn't usually done by the artist, but there's enough unity in all his work--especially Parker--that I'm confident he at least had a very strong hand in directing it.

I think Cooke's use of color is his secret weapon. It gives form to figures and features that could otherwise appear two-dimensional and dull. Look at that Wonder Woman drawing immediately above left. She's lit by blue light from the left and pink light from the right ("chiaroscuro") that makes her pop off the page. Cooke's characters are dressed in bold primary and secondary colors, as they should be, but there's always a haze or shadow to mute them. Backgrounds are subdued. His artwork feels light and bright but never garish.

|

| A painting by Cooke for New Frontier. |

Cooke's colors reminds me (and perhaps only me) of the work of the mid-century master Mary Blair, most famous for her work as a concept artist for Disney. They shared a thoughtful use of lighting to give life and form to fairly flat, almost geometrical, shapes. In any case, color is a key reason Cooke's work is instantly recognizable as his and no one else's.

|

| Mary Blair studies for Disney's "Peter Pan" and "Cinderella." |

Fun

Virtually every summary of Cooke's work uses that word, exemplified by both his art and his writing. Not that the stories he told were always light and funny. Parker was a hard-boiled noir detective, and Cooke's New Frontier version of the Justice League took some dark and serious turns.

Yet everything he did had a stylistic lightness and liveliness that never let his tales tip into grim, gory, or depressing. When appropriate for the story, nobody ever had more fun being a superhero than Cooke's characters.

|

| Again, look at the use of color. |

No need to take my word for Cooke's attitude toward storytelling when we have his. At a WonderCon panel in 2015, Cooke spoke on the state of today's superhero comic book business:

I can’t really read superhero comics anymore because they’re not about superheroes. They’ve become so dark and violent and sexualized. I think it’s a real wrong turn. I don’t know how a company like Warner Bros. or Disney is able to rationalize characters raping and murdering and taking drugs and swearing and carrying on the way they do, and those same characters are on sheet sets for 5-year-olds, and pajamas and cartoons . . .

I think the bravest and smartest thing one of these companies could do would be to scrap everything they’re doing and bring in creative people who would have the talent and were willing to put in the effort it takes to write an all-ages universe that an adult or a child could enjoy. If either one of these companies were smart enough to do that, I think they could take huge strides for the industry.

Cooke was a great talent, maybe even a necessary one. I'm sorry we lost him but I'm glad we had him at all.

Labels:

Obits

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)