The talk I gave at CarrierCon pulled together bits of insights I've gleaned about what it takes to be a creative professional. How do you jump the chasm between fan and pro? What do pros know that fans don't?

I figured it'd be a good topic because conventions like that draw young people who write their own stories, do their own art, make their own songs and videos and plays, and have ambitions to make their creativity more than a hobby. It turns out that I have some thoughts, and I wanted to share them here as well.

I introduced myself not just as a graphic novelist with three published books and another on the way, but as someone who's done many different types of writing, from newspaper reporting to science writing, for more than 30 years. The version below began as a PowerPoint presentation, intended to be delivered in bite-sized bits, so it may read a little choppy. I hope it's useful.

First, everything I'm about to say is just my humble opinion (JMHO). Everybody's fan-turned-pro story is unique. Every pro I know made it in some different, weird way. This may not apply to you. Take and use what works for you and forget the rest.

All pros began as fans! To prove it, here's an embarrassing photo of me posing with a tempera painting of Doctor Strange that I did around age 13.

Pros know what you're going through because they've been you. They probably still are.

First Important Advice

DO THE WORK.

DO MORE WORK.

DO EVEN MORE WORK.

I can't tell you how many people call themselves writers but never write, or call themselves artists but never create art. Just doing anything at all already puts you way ahead of the posers.

Then the hard part: show it to strangers. Push it out into the world however you can. It needs to be seen by people other than your friends and mom--people who aren't obliged to love it. Online, publishers, zines. Pass it out on street corners.

Start small. Make content for a blog or Instagram account, an article for your school paper, a photo for a work newsletter, a drawing for a softball team.

Turn many small things into a big thing.

Turn many big things into a bigger thing.

Build a PORTFOLIO. This is how you show people what you can do. It'll have examples of your very best stuff. A portfolio should be a changing, living document that improves as your skills and work improve.

I love Mark Twain's advice for aspiring writers:

I think Twain's right, although that puts Mark and me at odds with those who say creative people should never work for free--that they should value their time and effort as much as any professional. "Work for exposure?" goes the meme. "People die from exposure!" I understand but am also practical. You're not a pro yet, and volunteering may be necessary to start building a portfolio and get a foot in the door. The distinction I'd make: do gratis work if it serves YOU. Don't let yourself be exploited, but if you see it as part of a professional growth strategy, I say do what you've gotta do.

Others may disagree.

Learn How to Take Criticism

I'll now embarrass myself with another photo to make a point.

My first job out of college, I was a reporter for a small daily newspaper. You can tell how long ago that was by my brown hair and the green cathode ray tubes. That job gave me a thicker skin. I remember one day when an editor and I were slashing and reassembling a story I'd written, and I didn't get defensive about it. It wasn't personal, we were just working together to make my story better. I felt like a professional.

Here are some things NOT to say in the face of criticism:

"I meant to do that."

"You're not reading it right."

"It's not done yet."

"This isn't my best stuff."

I understand the impulse; I may have said some of those things myself. But if a reader doesn't understand you, that's your fault, not theirs. If it's not done or not your best stuff, why are you wasting their time with it? Stand behind your work! Say, "Yes, this is my best stuff!" It may not be what they like or need, but be proud of what you've done.

If someone is doing you the great favor of giving feedback on your work, SHUT UP AND LISTEN! Don't argue with them!

My personal experience: 19 out of 20 people who ask my opinion of their work really want me to tell them it's wonderful--perfect!--and they don't need to change a thing. That other 1 out of 20 has the attitude of a pro.

My experience matches Mr. Gaiman's. If one person identifies a problem, well, consider it, but maybe they just missed something. If two people identify the same problem, then you've got to fix it. The actual fix is up to you to figure out, not them.

It took me a while to realize why I consider my book editor, Charlie Kochman at Abrams, one of the best editors I've worked with. He'll find something that doesn't feel right or brings him up short or just doesn't work, but he always leaves the solution up to me. Then he either says "Yep, that does it" or "Nope, not there yet" and we move on. There are parts in all my books where I genuinely couldn't tell you which of us did what. Charlie makes me better without leaving fingerprints. It's a gift that good editors have.

Fanfic

Not a fan.

I want to differentiate between fan fiction and derivative works.

People create original work derived from the Bible, King Arthur, Shakespeare, Frankenstein, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes . . . for example, Dante's Inferno, Twain's Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, a thousand riffs on Romeo and Juliet such as West Side Story. Derivative works that build on legally available inspiration can be great pieces of art. I don't consider that fanfic.

Fanfic, by which I mean a story set in other creators' intellectual property, is fine for fun, friends, self-expression, and appreciation for stories and characters you love.

It's an OK way to get a feel for how storytelling and structure work.

BUT it's a poor shortcut past learning how to build worlds and develop characters yourself.

If you write Naruto fanfic, you don't have to explain how these characters, their relationships, and their abilities work. You just plug into a universe that already exists.

If you write Star Trek fanfic, you don't have to explain how a starship works. You say "Warp 5" and it goes. But what if you write a spaceship story that isn't Star Trek? Then you have to ask and answer some questions that have storytelling implications. Does your spaceship go faster than the speed of light? How? Maybe it doesn't, which means your spaceship has to operate within a solar system or maybe takes centuries to travel between stars. Or maybe your characters project their minds across the galaxy or communicate via quantum telegraphs. Now instead of leaning on someone else's universe, you're building something new and entirely yours.

I only realized when I put these images of Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter together that both universes have wizards and elves. But Gandalf is different from Dumbledore, and Legolas is very different from Dobby. Your wizard-and-elf story in one universe will be different than in the other, but the point is that neither universe is yours. You're building on someone else's foundation as a framework for your story.

Instead, take those inspirations and create your worlds. Put your twist on them.

One of my favorite examples is ElfQuest by Wendy and Richard Pini, which for 40 years has been telling stories about a world of elves. These aren't Tolkien elves and they certainly aren't Rowling elves (which they predate by decades). The Pinis created completely new characters living in a rich, deeply detailed world with their own societies, cultures, languages, spirituality, and relationships with each other and nature. It's a tremendous body of work built up over many years and books.

The critical point is that it's theirs. The Pinis don't have to ask permission of the Tolkien estate or J.K. Rowling to tell new stories. They don't have to send Tolkien or Rowling a check when they do. It's their world, their characters, their intellectual property to do with as they please.

A big problem with fanfic: with very, very few exceptions, you'll never be able to legally publish it.

(This is where someone points out that Fifty Shades of Grey began as Twilight fanfic. It's an exception that proves the rule, and also supports the point that E.L. James couldn't publish Fifty Shades until stripping out everything that smacked of Twilight.)

Fanfic is not (generally) the way to a professional career.

Instead, draw inspiration from LIFE: history, science, politics, travel. Your own lived experiences. Not other people's stories.

That will make your work stand out.

The cliche advice is "Write what you know!" I always amend that to add, "As long as what you know is interesting!" I think it's incumbent on writers, and creative people in general, to have broad curiosity. Take in everything you can about the world then filter it through yourself so that nobody could have written the same thing in the same way.

Ideas

Ideas are great, but are not as rare and special as you think.

I occasionally get an email that goes like: "I have a great idea for a book! You only need to do all the writing and drawing and find someone to publish it! I'll cut you in for half!"

The idea is the easy part. All that other work is the hard part.

I got an inkling of that when I had a chance to pitch stories to the producers of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, and Voyager. I pitched maybe 40 or 50 stories and never sold one, never got my name on screen, but I learned a lot. I can't tell you how many times I got two sentences into my most outlandish science-fictiony plotline when the producer raised his hand and said, "I've gotta stop you. We started filming that last week." And they were right! Six months later I'd see episodes that were so similar to my ideas I'd have been sure they'd ripped me off if they'd ever heard them in the first place.

Ideas are common. What matters is what you do with them . . . how you execute them.

Ways Pros Differ from Fans

1. Pros can take criticism from people they respect, or who are in a position to pay them.

The first point is important: bad criticism from an idiot can be very harmful, but good constructive criticism is gold if you're mature enough to accept it. The second point is also important: sometimes you've got to give the client what they want even if they're an idiot.

2. Pros treat it like a job. They don't wait around for inspiration to strike. Don't be precious about it, just put your butt in the seat and do it.

3. Pros know that being reliable, responsive, and a good collaborator is just as important--and maybe MORE important--than being talented.

When you're mystified how people you consider pretty mediocre keep getting jobs, the reason may be that they hit their deadlines, meet their commitments, and are easy to work with. Not being a jerk can get you a long way in whatever profession you're in.

4. Pros are not afraid of imperfection. They know their work won't be perfect but they do it anyway.

In my opinion, a lot of "writer's block" is fear of imperfection. As long as you don't start, the thing in your head is perfect. When you pull it out of your head and make it real, it won't be perfect anymore. I think it's very important for creative people to give themselves permission to be imperfect. To even suck once in a while. You can always improve it later, and nobody needs to see your failures but you. Start something, even if it stinks.

I was struck by that watching Peter Jackson's Beatles documentary,

Get Back. It shows the Beatles putting together an entire album in a month. The Beatles didn't worry about perfection. Oh, they worked a song over and over until they got it good enough--and because they were the Beatles, "good enough" was better than pretty much anybody else--but then they recorded it and moved on.

Don't waste 20 years trying to make it perfect. You may know someone with a novel in the drawer or a song on their computer that they work and rework and rework for literally years. Those people will never achieve the perfect creation they seek. In fact, they're more likely to beat all the life out of it.

Do your best. Finish. Learn from it. Move on.

The Bravest Creative Acts I Know

1. Beginning a new project knowing you have months or years to go.

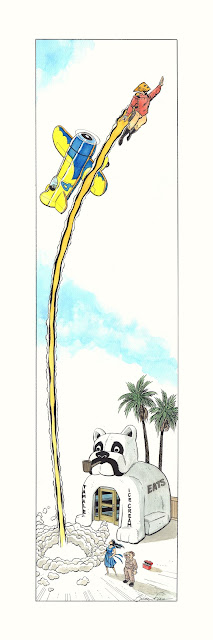

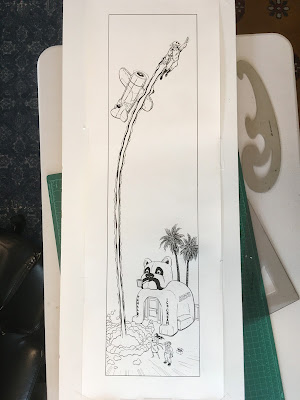

When I start a new graphic novel, making the first ink mark at the top left of Page One, I heave a little sigh because I know I've taken the first step on a thousand-mile journey. It's daunting. My advice: break it into pieces. Authoring a 300-page book may seem impossible, but anybody can write eight pages. Or four. So do that. Then do it again. Then keep doing it. Manageable bite sizes. Or, as Anne Lamott wrote, bird by bird.

2. Showing your work to someone who might rip it apart. It's the best you can do but what if it's not good enough? You're wearing your heart on your sleeve, inviting a stranger to stomp on it. That's why it's brave.

3. Sending your work into the world beyond your control. Your work is your child, your heart. The world can be cruel and scary, and when your work is out there it can go in directions and end up in places you never anticipated--or worse, be completely ignored. You have to let it go.

Sometimes I hear about places my books have been and feel a little envious. They're out there having adventures I never will! Occasionally they send back a little postcard, which I appreciate.

4.

DO THE WORK.

DO MORE WORK.

DO EVEN MORE WORK.

Can't overstate the importance of that.

So You're Ready!

You have the discipline, you're producing work, you're getting good feedback from readers, online fans, TikTok or YouTube viewers, whomever.

NOW WHAT?

One option: Do it yourself.

Self-publish, eBooks, print on demand. You're responsible for distribution, marketing, accounting . . . all the business side. Not everybody's cup of tea. You do all the work but keep all the money.

Or: You may be able to submit directly to a publisher or outlet. List a dozen that put out work that's kind of like yours. Check their online submission guidelines. FOLLOW THEM.

Or: Depending on your medium, you may want or need an agent.

An agent represents you to publishers, studios, etc. for a percentage of the income they bring in for you.

An ethical agent will not charge you a fee up front! They don't make money until you make money! Don't fall for crooks!

How to find an agent? I don't know. I don't have one.

But I know people who've gotten agents via referrals from friends. There are trade and professional organizations you can look up. Author's acknowledgments. Or you can do your own Google research.

Agents specialize. Find the ones who represent your kind of work.

Check their online submission guidelines. FOLLOW THEM. (Sound familiar?)

Here's one thing not to do: Don't bug your favorite pros to help you. Honestly, there's very little they can do.

Even if I think your work is great, I don't know you. I don't know if you hit deadlines, play well with others, are a sane and functional human being.

I can only think of maybe three times I've contacted an editor to vouch for and try to open a door for a friend. The number of book deals that resulted in: zero.

YOUR WORK HAS TO SPEAK FOR ITSELF.

You won't believe me, but I promise: editors, publishers, producers are hungry for good, new content. They need you even more than you need them.

You Get an Offer

Holy Moley! Congratulations!

Don't sign a contract right away.

If you have an agent, they should watch your back. If you don't, hire an attorney.

You are expected to negotiate! They won't be offended or rescind their offer. If they do, you didn't want to work with them anyway.

Notice I said "work with" instead of "work for." They're not your boss and you're not their employee. You're eyeing each other to decide if you want to be business partners.

Unless . . .

Understand "work for hire." That means the person or company you're working for keeps all the rights. If you're hired to write or draw Batman, it doesn't matter how good you are or how long you do it, you'll never own Batman, or get to write and draw your own Batman stories after you leave DC Comics. You're work for hire; they pay you to do a job and that's the end of it. That's fine as long as you know what you signed up for.

In general, keep all the rights you can.

What a lot of non-pros don't understand is that, at the moment you create something, you own all the rights to it. You hold the copyright, the North American publishing rights, the worldwide publishing rights, the digital rights, the TV and movie rights, the plush toy rights, the cereal box rights. They're all yours.

A contract is a tool for someone else to pay you for those rights. You have something they want. You can let them have whichever rights you want and keep whichever you want. There will be some they'll insist upon, and you'll have to decide if you're OK with that (you probably will be). Others they won't care so much about.

But unless you're doing work for hire, always--always always--retain the copyright to your creations.

I have friends who signed away their copyright, then had to watch as strangers elbowed them out and took over the characters they created. It's heartbreaking.

Trust me: A bad deal is worse than no deal at all. Walk away from a bad deal, even if it's the only deal on the table.

Don't let yourself be exploited!

Summing Up

1. Do the work. No excuses.

2. Put it out into the world any way you can.

3. Take criticism and rejection gracefully.

4. Act like a professional even if you aren't one yet. Build a good reputation. People remember.

Most Important

Be authentic and honest in your work. I deeply believe that audiences crave authenticity. They want to feel like they're in a conversation with you, like they're getting a glimpse into your heart and mind.

An audience can detect bullshit. Don't peddle it to them.

Trying to strategize what's "hot" and what "the market wants" rarely works. By the time you figure it out, everyone's moved on to something else. Follow your own peculiar passions to create something that people didn't even know they needed.

Figure out what makes you unique and lean into that. Harness your "weird."

I feel this very strongly. Being weird can be a social handicap when you're young but an invaluable tool as you grow. If you've got a passion for collecting bottle caps, if you love bottle caps with all your heart and you know all there is to know about them, and if you can explain to me what's cool about bottle caps and why I should care about them, too, I'll be your fan for life (this is Malcolm Gladwell's career). I'd much rather read your bottle cap book than the thousandth Lord of the Rings pastiche about a gang of kooky characters bumbling through a magical quest.

Tell the stories only you can tell.

Stand on your little island and plant your flag. Especially in the Internet Age, people will find you.

Even More Important

As I said at the start, all of this is JMHO. Take and use what works for you and forget the rest.

Also, I'm always open to the possibility I'm wrong. Happy to reconsider. Let me know.

And good luck!