1. My Day Job: multiple year-end deadlines are piling up, and all of my clients believe they are my sole top priority, just as I groomed them to believe. Heh heh heh. Unfortunately, now I have to act like it.

2. Mystery Project X: In any spare time I can find, I am pencilling pages. I thought I'd try something different this time. My plan is to pencil the entire book, then go back and ink it (usually I ink as I go, finishing pages in batches of three or four). I'm hoping it'll produce some stylistic continuity from start to finish, allow me to fold in any great new ideas that come up, and be a bit more efficient. We'll see; I may change my mind. It's all still being done on spec, with no contract or commitment from a publisher (although interest from more than one). I have faith.

3. Whatever Happened to the World of Tomorrow: With luck, we'll have one or two good things happen in 2012 that I'm working on now and can tell you about later.

Despite my busyness, I still feel a nagging obligation to give you a reason to visit once in a while. So with your indulgence (or without it, just watch me!), from time to time I'll dip into the archives and post a re-run. Since I've been blogging since July 2005, I've got a big backlog of perfectly swell essays little seen or long forgotten. I'll try to pick good ones.

Here, lightly edited, is a post I wrote in September 2006 about something I learned from failing. At the time, Mom's Cancer had been out a few months and I'd just started working on WHTTWOT.

I've written about my great affection and appreciation for the original "Star Trek" before, but in fact my relationship with the series goes a bit beyond that. This is a story I don't tell very often--mostly because it ends in abject failure--but I did talk about it during my 2006 Comic-Con Spotlight Panel and I think it gives some insight into how I approached the writing of Mom's Cancer.

I've written about my great affection and appreciation for the original "Star Trek" before, but in fact my relationship with the series goes a bit beyond that. This is a story I don't tell very often--mostly because it ends in abject failure--but I did talk about it during my 2006 Comic-Con Spotlight Panel and I think it gives some insight into how I approached the writing of Mom's Cancer.The 1960s' "Star Trek" was followed by another series that began in 1987 called "Star Trek: The Next Generation." It ran for seven seasons. I enjoyed the show as a fan, though never as passionately as I did its predecessor, and around the beginning of Season Six I learned that the show would consider scripts from unagented writers. This policy was unique in all of television and the news hit me like a thunderbolt. In a few weeks I came up with a story, figured out proper TV screenplay format, and sent off a full script with the required release forms. Shortly afterward I followed with a second script, the maximum number they allowed.

I don't know how much later--surely months--I arrived home to a message on my answering machine. "Star Trek" wanted to talk to me. Neither of my scripts were good enough to actually shoot, but they showed enough promise that they were willing to hear any other ideas I might have. Would I care to pitch to them?

Yeah. I think so.

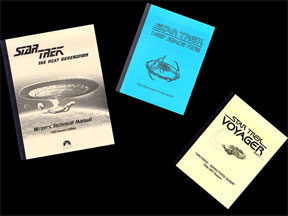

Paramount sent me a three-inch thick packet of sample scripts, writer's guides, director's guides, character profiles, episode synopses: all the background a writer would need to get up to speed (not that I needed them--I'd been up to speed since 1966). I spent several weeks coming up with dozens of ideas, distilled them to the five or six best, and made the long drive to Paramount Studios. Just getting onto the lot was a small comedy of errors: the guard at the gate didn't have my name on the list and I'd neglected to ask which building and office I was supposed to report to. Unlike anyone who's worked in Hollywood in the past 30 years, I wore a tie and sportcoat--a bad idea on a hot day when I was already inclined to sweat prodigiously. But I eventually made my way to the office of producer Rene Echevarria and threw him my first pitch. He stopped me after two sentences.

"We started filming a story just like that last week."

Crap. That was the best one.

Pitches two, three, four and five fared no better. After desperately rifling through my mental filing cabinet for any rejects with a hint of promise, I was done. In and out in less than 30 minutes, weeks of work for naught.

Still, I went home satisfied that I gave it my best shot. I wrote Rene a letter thanking him for the opportunity and expressing a completely baseless hope that he might give me another chance someday.

I got the next call a few weeks later. Rene had gotten my letter, looked over his notes, and decided that, although none of my pitches were good enough to shoot, I merited another shot.

Months later came my second try. By then I was smart enough to spare myself the drive and pitch by phone. If I remember correctly, Rene liked a couple of my stories enough to take them to his bosses, but by this time the series was into its final season and the available episode slots were filling fast. In anticipation of the end of "The Next Generation," Paramount was already producing a successor series, "Deep Space Nine." In my last conversation with Rene, when it was clear "The Next Generation" was done with me, I asked if he could arrange for me to talk to "Deep Space Nine." He was bewildered.

"Why would you want to pitch to those guys?" he asked.

Nevertheless, I soon had an appointment to pitch to those guys, got another thick packet of space station blueprints and character bios, and started writing. I parlayed that opening into several pitches over the show's seven-year run, most to the very professional, generous and kind writer/producer Robert Hewitt Wolfe. And when Paramount started production on the next "Star Trek" series, "Voyager," I tried my old trick on Robert.

"Why would you want to pitch to those guys?" he asked.

So I got more packets of cool stuff, more experience, and more rejection. Although they liked some of my ideas enough to mull them over, I never got close. It was exhausting. At last, after eight or nine years and forty or fifty stories, "Star Trek" and I mutually agreed we'd had enough of each other and parted ways.

Lessons in Writing

Here's my point (and I do usually have one, eventually): even as a complete failure, my experience pitching to "Star Trek" made me a better writer. What I realized was that the stories they quickly rejected focused on some science-fiction high-tech premise or plot twist, while the stories they liked focused on the characters. If I said something like, "Captain Picard starts the story at A, experiences B, and as a result grows to become C," I had their attention. I had to be hit over the head several times to realize that a good story isn't about spaceships or aliens or ripples in the fabric of space-time, but about people.

That sounds blindingly obvious, but I realized how unobvious it was as I talked to friends and family about the experience. As soon as someone hears you have a distant shot at actually writing a "Star Trek" episode, they can't wait to share their ideas with you (never mind how fast they'd sue if you actually used one). And literally without exception, every idea I heard from someone else was about a spaceship, alien, or ripple in the fabric of space-time. Not one that I recall even mentioned a character, how they'd react to the situation, or how they might be changed by it. Once I learned to look for it, it was striking.

These were lessons I internalized as best I could and took into the writing of Mom's Cancer. I realized early that my story couldn't be about the medical nuts and bolts of cancer treatment. First, because there are too many treatment options for anyone to cover; second, because I knew such information would be obsolete very quickly; and third and most importantly, good stories are about people. My book isn't about radiation and chemotherapy and cancer, but about what those things do to a family. If something I scripted or sketched didn't drive my mother's story--if the plot didn't serve the characters--I cut it.

Whatever success my books have had and will have, I think that's the key. With due gratitude to all the Treks.

.

2 comments:

Brian, you comment-fishing pro - - you know that any mention of Star Trek will elicit a massive reply thread. Kudos. :)

Of course, the heart of any Trek story is the trajectory of the characters. In TOS, we had Kirk knowing that his love, Edith Keeler, must die - - and so he let her die by grabbing the man who would save her. Commodore Matt Decker had to deal with the loss of his crew on the 3rd planet of System L-374, while he was locked helplessly in the control room of a wrecked starship. Spock wound up in one story believing he killed his Captain, and his friend, over an uncontrollable infatuation with a Vulcan woman. The technology and the setting were all science fiction, but the human stories have been with us since Shakespeare.

I keep wondering if it's easier or more difficult to write fiction over nonfiction. Working on my Sekrit Space History Book, I've noticed that it's difficult to maintain an organizing sensibility, as the principal cast keeps dying or leaving the storyline over time. The more I expand the timeline of this story, the more I realize how brilliant your slowly-aging Pop and The Kid are as narrative hosts in WHtTWoT.

There was probably a point I was trying to make in all this but I forget now. Anyway, awesomely cool stories about your intersections with the Trekverse! Thanks for sharing the tale.

"The Doomsday Machine" is a good example. Ask someone what it's about, and they'll say it's about a giant planet-eating machine. No it's not. It's about Decker being driven mad with guilt and grief, Spock standing up to him to save his ship, and Kirk's frustration, resourcefulness and courage. That's what makes it one of the better-regarded episodes.

The obvious challenge with non-fiction is that real life rarely follow neat arcs with tidy messages. But everyone still has desires, goals, successes and failures. There's drama, comedy and tragedy in that. Your Sekrit Space History has an arc of its own--a beginning, middle and end--with episodes of high-stakes risk and drama. It could work! And I appreciate the nice words about Pop and Buddy.

Post a Comment