First, read

yesterday's post to catch up. Ready?

(By the way, I don't expect everyone to read these posts. Don't feel guilty for passing them by. But I bet they'll still be getting Google hits months from now!)

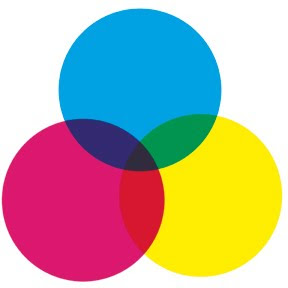

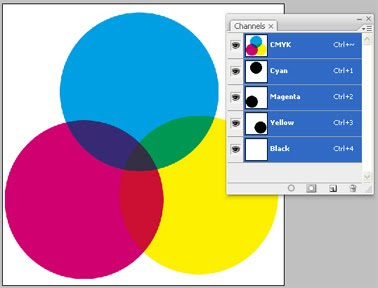

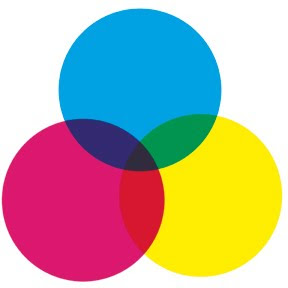

Color process printing is typically done with four inks: cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, abbreviated "CMYK" (I understand the "K" actually stands for "Key Color"--which is always black). Most of the color printing you see in books, magazines, newspapers, billboards, posters, and cereal boxes is CMYK.

The little color wheel up top shows how that works: overlapping transparent inks produce all the colors of the rainbow. C+Y = green, Y+M = red, M+C = violet, and C+Y+M = dark gray. When you use the halftone process to made different shades of those base colors, and add different shades of gray as well, you end up with a pretty large (but finite) palette.

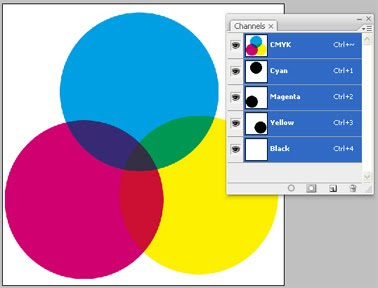

Here's a Photoshop screenshot to help illustrate my point. See the three "Channels" showing cyan, magenta and yellow? The little thumbnail images with each channel show the contributions of cyan, magenta and yellow to the large image--the three big circles. We'll be using Channels later and I wanted to offer a peek.

I'm going to write about CMYK vs. RGB for a second. "RGB" is "red-green-blue," the colors of light your computer monitor generates to compose images. The big difference between RGB and CMYK is that RGB mixes

light while CMYK mixes

pigment. Remember from junior high science how combining red, green and blue light makes white light? Well, combining red, green and blue (or cyan, magenta and yellow) pigment makes mud.

So if you're doing artwork that will only be seen on a computer--maybe a website or PowerPoint presentation--go ahead and work in RGB. But if there's a chance it'll be professionally printed someday--any chance at all--I'd advise working in CMYK from the start. Pretty much all CMYK colors can be converted to RGB equivalents, but a lot of RGB colors don't convert to CMYK. One day you'll try to print out a nice poster of your best webcomic and the colors will look like yak barf. I warned you.

Now let's do a color separation and make some dots! NOTE: there are other, better ways to do color separations in Photoshop. I did it in this labor-intensive, hands-on fashion because I wanted to accomplish some particular comic-booky effects with my pages. Nobody does

real color separations this way, but my original anonymous questioner asked how I faked it for my book. This is how I did it.

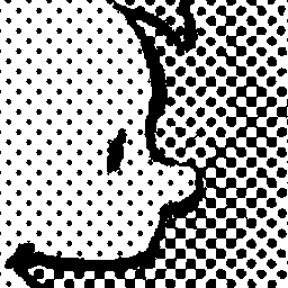

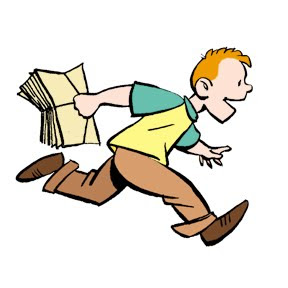

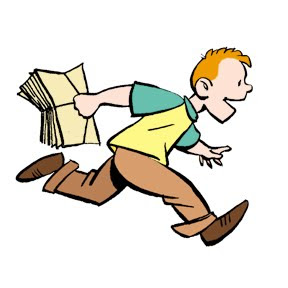

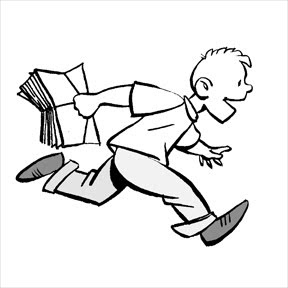

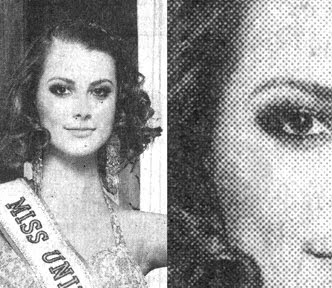

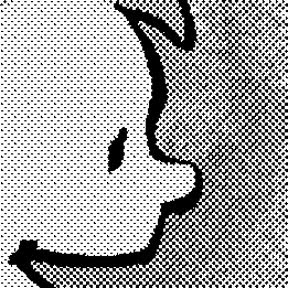

Here's our guinea pig, familiar from yesterday even if you don't remember Buddy from my book

WHTTWOT. I deleted the gray ink wash background because we already dealt with grayscale halftone.

Here are the four CMYK channels that comprise that image:

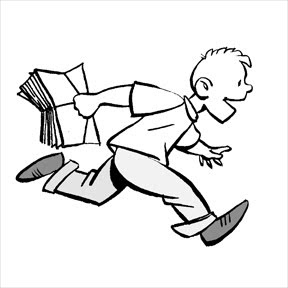

Black. This is the basic line art, the part I drew with ink. Notice that there's also some gray that darkens the browns in Buddy's shoes and pants.

Cyan. But wait a second! If this is the cyan channel, why is this picture gray instead of cyan? Because the intensity of the gray indicates how saturated the cyan is. Remember, CMYK is meant for a printing press; this separation defines how much cyan ink the press will put on the paper. It's dark where the cyan is darkest, like on Buddy's turquoise shirt sleeves, and light where it's lightest.

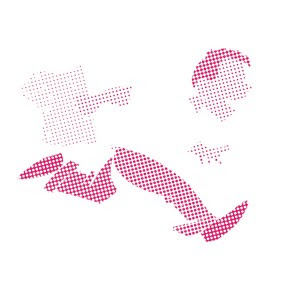

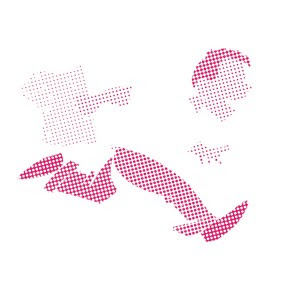

Magenta. There's a bit in his hair, as you'd expect, and some in the brown of his pants and shoes. None in his shirt.

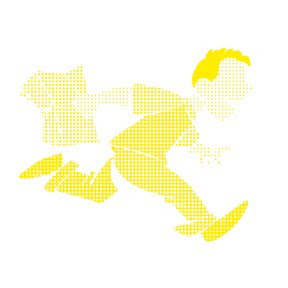

Yellow. Buddy's orange-red hair has a lot of yellow in it. His shirt is entirely yellow (notice there's no cyan or magenta in it). His flesh tone is a mix of magenta and yellow, while his brown pants and shoes combine all four colors.

Making Color HalftonesHang in there. Now I'm going to take each CMYK channel individually, turn them into halftones like we did yesterday, then recombine them at the end.

I'll use the cyan channel as my example. Here it is again, same as above:

In Photoshop, right-click on the cyan channel (on the small panel I showed above), click "Duplicate," and from the "Destination--Document" pull-down menu select "New." A new window will open looking just like the image above.

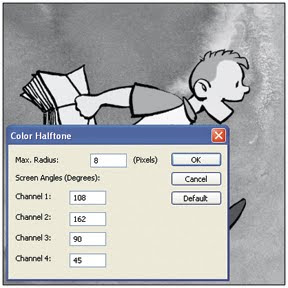

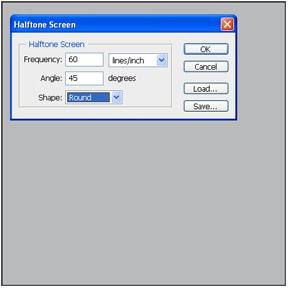

Like we did yesterday, convert to Bitmap mode, then Halftone Screen. You should assign each screen a different angle at 15 degree increments to keep their dots from perfectly coinciding. For

WHTTWOT (based on old printing practices) cyan is 105 degrees, Magenta 75 degrees, Yellow 90 degrees, and Black 45 degrees. Since we're doing cyan now, enter 105 degrees and whatever frequency that gives the dotty result you want:

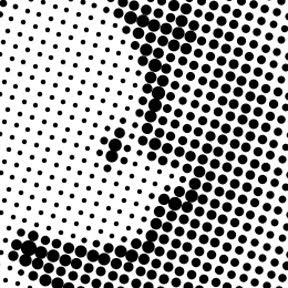

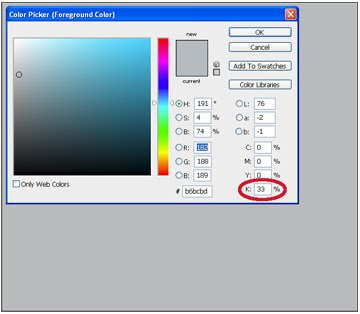

See, just like yesterday. Now we're going to make it blue. Convert from Bitmap to Grayscale to CMYK mode. Then "Select Color Range," sample one of the black dots in the image, and "Edit--Fill" with 100% cyan (and 0% everything else):

Same for the other three channels (the order doesn't matter). Notice the different screen angles of the dots:

Same for the other three channels (the order doesn't matter). Notice the different screen angles of the dots:

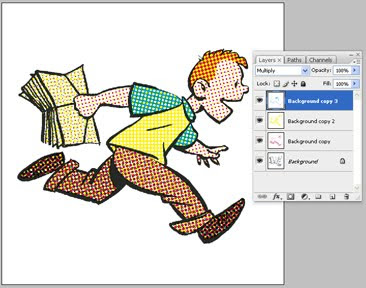

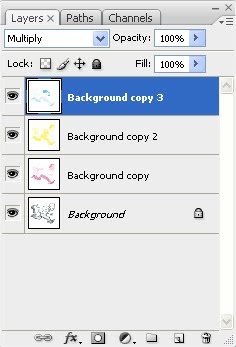

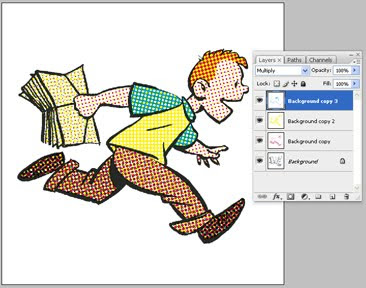

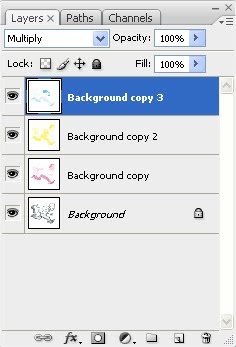

Now we're going to combine these four images into one. Copy or "Duplicate Layer" so they're all lying on top of each other in one file. Picture it like this: you've got four layers of paper, each printed in cyan, magenta, yellow or black, all stacked up.

Now imagine making the paper transparent so you can see all the layers! That's done via the "Layers" control panel shown immediately below and in close-up. See the word "Multiply?" For each layer (except the bottom one), change that setting from "Normal" to "Multiply." Now your layers are transparent and the dots of color are free to mix and blend.

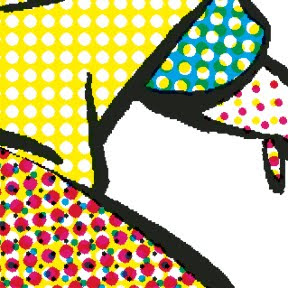

Below is a super close-up of our picture, showing how it works. Using nothing but cyan, magenta, yellow and black dots, we've produced turquoise, orange, browns, and peachy skin tones. Since your four colors are isolated on four different layers, it's easy to mess around with one color without changing the others. That's how I "printed" my old comic book colors out of register and introduced various blobby, smeary "defects."

Then if you're doing a graphic novel with 50 pages of old-timey comic book to fake, just do the same thing 49 more times and you're good to go. Good luck! I'm not dumb enough to try it again.

Completely unrelated but kind of cool: you're also now qualified to begin your second career as an art forgery and counterfeiting expert. While there's a long list of things that are reproduced by four-color process printing, there are a lot of things that aren't. For example, money. In addition, authentic silk-screen prints are made by squeezing many different colors of ink through stencils adhered to, yes, a silk screen. Some great old posters used 20 or more different inks to produce all their colors. If you look closely at a poster that says it's silk screened and see arrays of tiny dots like those in the image above, it's a reproduction. Likewise antique prints and etchings. Before the 20th century, printmakers created shades of gray by engraving fine cross-hatching or stippling on their plates. If you look closely and see tiny irregular dots, that's hand-crafted stippling. If you see dots too small and perfectly aligned for a human being to make, that's a modern copy.

If that tutorial wasn't sufficient, Wikipedia has some entries on CMYK, four-color process printing, and halftone. Also, I didn't say anything about Trapping. As always, I welcome additions, corrections, and discussion from people who know more about it than I do. Go nuts. I'm tapped out.

HOWEVER . . . If you've read this far, you might as well go ahead and check out this post from July detailing how I applied these techniques to make a page of my book, including adding imperfections intended to mimic bad printing technology and 70 years of age. It's fun!

Black. This is the basic line art, the part I drew with ink. Notice that there's also some gray that darkens the browns in Buddy's shoes and pants.

Black. This is the basic line art, the part I drew with ink. Notice that there's also some gray that darkens the browns in Buddy's shoes and pants.

See, just like yesterday. Now we're going to make it blue. Convert from Bitmap to Grayscale to CMYK mode. Then "Select Color Range," sample one of the black dots in the image, and "Edit--Fill" with 100% cyan (and 0% everything else):

See, just like yesterday. Now we're going to make it blue. Convert from Bitmap to Grayscale to CMYK mode. Then "Select Color Range," sample one of the black dots in the image, and "Edit--Fill" with 100% cyan (and 0% everything else): Same for the other three channels (the order doesn't matter). Notice the different screen angles of the dots:

Same for the other three channels (the order doesn't matter). Notice the different screen angles of the dots:

Then I transformed the image from "CMYK" mode to "Grayscale" mode, and then to "Bitmap." You can't go directly from CMYK to Bitmap; don't know why. No big deal. Bitmap mode offers several options. We want "Halftone Screen." The window below pops up.

Then I transformed the image from "CMYK" mode to "Grayscale" mode, and then to "Bitmap." You can't go directly from CMYK to Bitmap; don't know why. No big deal. Bitmap mode offers several options. We want "Halftone Screen." The window below pops up.

To give some idea of the different looks you can achieve, here's the same image at half the halftone frequency above:

To give some idea of the different looks you can achieve, here's the same image at half the halftone frequency above: